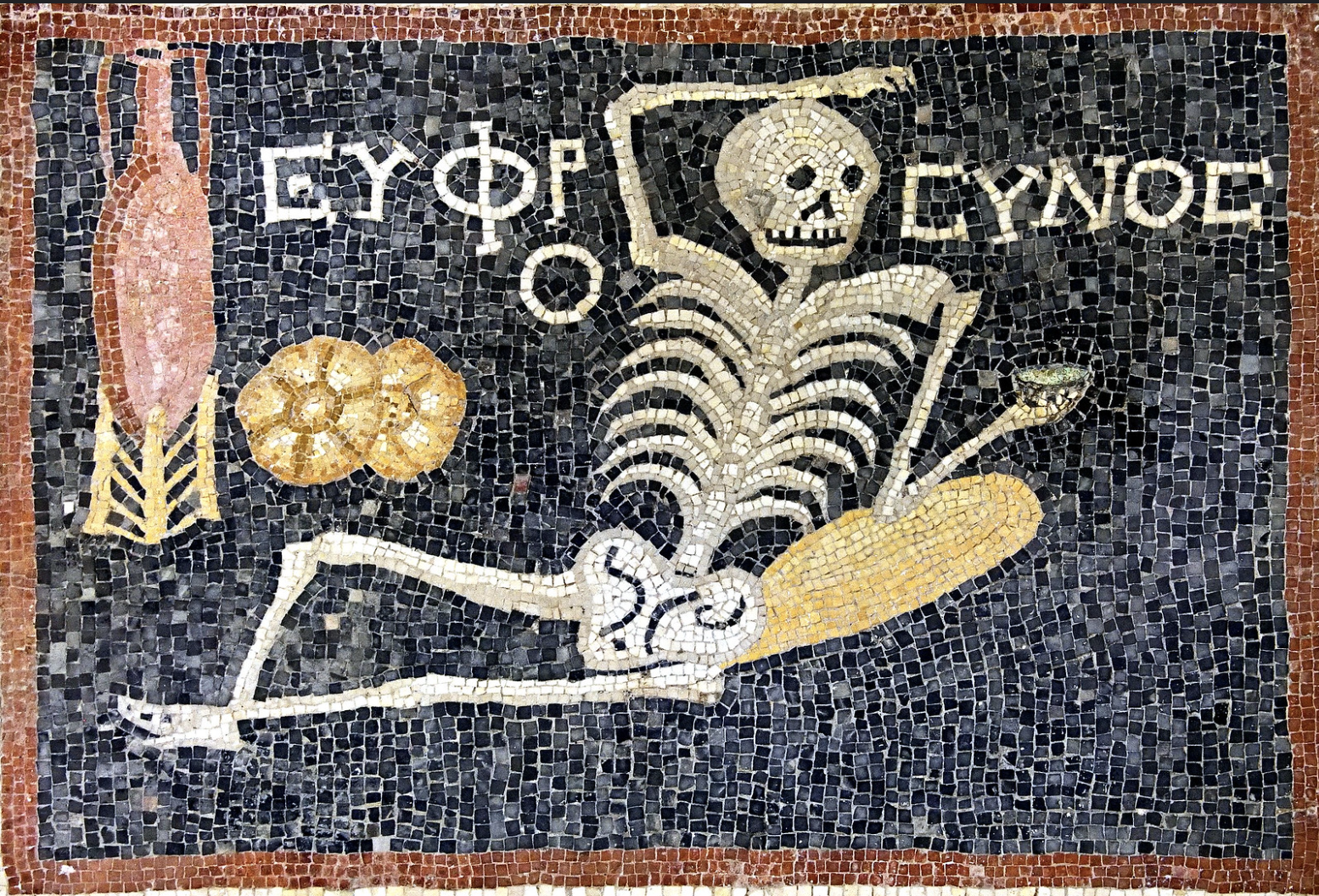

Image credit: Antakya Archaeology Museum – Roman mosaic, 3rd–4th century, ΕΥΦΡΟΣΥΝΟΣ, “Euphrosynos” (“Enjoy”)

part 2 of a series

It ends in s

Editors’ note: The typescript of the author’s latest installment arrived, per usual practice, via post in a brown envelope lacking return address. Unusually, a sticky note was affixed to the first page with the hand-written inscription, “Vide mama, sine notis!” Which, as best we can tell (our Latin not being what it once was), translates as “Look ma, no notes!” No doubt in response to our gentle admonishments against pedantry in the form of copious footnoting, which tends to depress readery. We will leave it to the reader to characterize what sentiment may be pregnant in the affixture, noting only herein that, indeed, no footnotes attributable to the author were noticed in this lengthy notation.

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is Man.

Placed on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the Sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the Stoic’s pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act or rest,

In doubt to deem himself a God or Beast,

In doubt his mind or body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reasoning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such

Whether he thinks too little or too much:

Chaos of thought and passion, all confused;

Still by himself abused, or disabused;

Created half to rise and half to fall;

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled:

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!– Alexander Pope, Know Thyself

Busy as you are, with all your obligations and pastimes, you probably have not reflected enough to know that you have an anthropology. A fixed sense of what sort of species yours is. And you’ve probably come by it dishonestly—without much thought. You may have inherited it, you may have come to it through your contingent experience, you may have had a formative thinker whose teaching you learned in adolescence (whatever type: philosophical, theurgical, biological, some combination) who gave it to you on a platter needing only consumption, so obviously true it struck you as being. However you came by it, you have it.

More to your embarrassment, you’re likely to have an extreme view (as those are simplest).

To one extreme: Humans are a horrible, violent species, much worthy of utter condemnation (though, if so, you might have done the universe a favor and offed yourself—before procreating). If that’s your anthropology, your intellectual hero would be Thomas Hobbes, or, if a religious type, John Calvin (aping the sainted Augustine). And this view can be given its appropriate Latin binomial: Homo necans, the killer species.

If you know nothing of Hobbes other than his famous quip, “Nature red in truth and claw,” then you would be doing better than most of your fellow citizens (some significant percentage of which have IQs under 80, you faring little better). Further knowledge of Hobbes being unnecessary in the present use case, beyond the fact that he very much considered you and all of you (himself?) as a part of that bloody nature. Which, you have to admit, has something to it (remembering slicing into that juicy steak and seeing, hungrily, a pool of diluted hemoglobin form on your platter, which, if not impolite, you would lick after finishing the flesh). Unlike enchanted Christians, Hobbes saw the agony of the beautiful hawk’s prey—and considered you among the hawks. Actually, a wolf among wolves, homo homini lupus.

If you know nothing of Calvin other than he was a somewhat bedazzling French theologian who managed to infect first Geneva, then the Sceptred Isle, then the New World (or some trajectory like that) with an invasive ideology, lucky you.

Hobbes needed a punishing sovereign, Calvin inherited a punishing god. Happy days.

To the other extreme: Humans are natural egalitarians, a peaceful sort, ruined by malign civilization, with all its political machinations. Here you are graced by such heroes as Rousseau and endless social science types (anthropologists, archaeologists and such) who see the advent of agriculturalism as an unmitigated disaster for your otherwise happy, hippy species, living in an evanescent saeculum of human flourishing.

Thence hierarchy, patriarchy, reduced physical stature, nutritional deficits, stress fractures from manufacturing foods and pots and tools, endless labor interrupted only by warfare due to defensible nests—a calamitous fall from the pristine state of nature: Eden, the Golden Age when Cronus ruled, the Laudes Italiae. A state of grace, which is more recently conceived to be gathering fruits and nuts by nurturing females (little ones riding on hips), with the males wasting time in occasional scavenging and attempts at hunting; loud, proud and generally useless beyond their conceptual contributions.

None of which is entirely true, but an imagined human innocence does suggest something lacking in its contrasting anthropology (Homo necans). Like egalitarianism, altruism (even indirect altruism), cooperation—the demonstrated characteristics of human societies you’re no longer allowed to designate as primitive. Something more like Hume envisioned (but you’ve read no Hume, which, fine).

Rousseau, proud of his middle-class (moyen) background, wrote in demotic French rather than Latin, thus robbing the world of a handy binomial. Had he less concern for literary virtue signalling and adopted the scholarly demotic, he may well have designated the species Homo naturalis, the natural race, or Homo innocens, the innocents. Whom he believed to have been corrupted by Hobbes’ Leviathan—the state, that coldest of all cold monsters.

Between the extremes are found various luminaries with their various binomials, more indicative of their domain of interest than an essential description of the species. So we have Aristotle’s Homo politicus (actually, it was πολιτικόν ζώον, “political animal”), John Stuart Mill’s Homo oeconomicus (selfish money grubber), Johan Huizinga’s Homo ludens (the player of games), Mircea Eliade’s Homo religiosus (the enchanted sort), Walter R. Fisher’s Homo narrans (teller of tales)….

With such a suite of options, you wonder, in an uncharacteristic spasm of curiosity, why did Homo sapiens stick?

The answer, as with so many, is to be found in the eighteenth century, when Carl von Linné (or, to his friends, Carl Linnaeus; to his admirers, Princeps botanicorum) found himself in Sweden, the son of a Lutheran minister and amateur botanist—a common pastime in times preceding the wireless.

If ever there were something in a name, Linnaeus has it. Carl’s father, Nils, was the first in his line to adopt a fixed surname, said adoption being a requirement for matriculation to Lund University. Nils would have been known as Nils Ingemarsson after his father, Ingemar, had his hand not been forced by university bureaucrats. As it was, Nils chose Linnæus, a Latinized rendering of the Swedish lind for linden tree, of which Nils had fond memories, a giant iteration having shaded his family property. And so Nils bequeathed his son a botanical surname. But for that, the Prince of Botany would have been known as Carl Nilsson.

The history of the naming of things starts with a certain irony. Adam was told to focus on zoology by his tutoring divinity; it was botany that led to his undoing. (What you wouldn’t give to have the bestiary Adam compiled. As it happens, you are told of only one of his nomina: Eve. Take from that what you will.) The Prince of Botany’s signal accomplishment, conversely, was a zoological innovation, classifying humans as one species among other primates. Surprised? Likely so, as you are under the vague impression that Linnaeus’s greatest achievement was inventing the now canonical binomial naming system. In which case you would be largely incorrect, as Gaspard Bauhin was the first to accomplish that bureaucratic feat, 200 years before Carl.

To be fair, Linnaeus systematized binomial nomenclature—no small feat—and established the rules for its extension to all the things, living and otherwise. There was a first name, the generic name, identifying the genus; and there was a second name, the specific epithet, typically (though not always) distinguishing the species from other members of the genus. Thus we have Hyacinthoides italica, the Italian bluebell, a flowering plant, to be distinguished from its Spanish cousin, Hyacinthoides hispanica. And of course, Tyrannosaurus rex, the king of the Tyrannosaurini.

Though it must be noted, Linnaeus was not entirely consistent in applying the binomial straightjacket. Sometimes a third world was required to distinguish one thing from its related other, hence trinomial nomenclature. As an example, to distinguish a dog from a wolf, Linnaeus added a trinome; the wild Canis lupus became the domesticated Canis lupus familaris. Which occasionally led to ridiculous trinomes as Linnaeus’s system was elaborated over time. So, to distinguish a particular subspecies of gorilla (the western lowland sort) from its cousins (Eastern lowland, Mountain, and Cross River sorts), we now have Gorilla gorilla gorilla. Still, three counts as better than a near infinity of terms, as was common practice in Linnaeus’s day. The humble milfoil required a mouthful: Achillea foliis duplicato-pinnatis glares laciness linearibus acute laciniatis, which translates “Yarrow leaves [are] double-pinnate, with linear, acute, laciniated glabrescent [hairless] lacini.” The Prince of Botany whittled this down to Achillea millefolium. That alone being worth his crowning.

Glabrescent causes you some concern, as you age…. As do other things, with Latinate, demotic and acronymic descriptors.

If naming might be considered a way of knowing, organizing what is known might be considered a way of subduing. Which, after all, is was the ennobled species was meant to do. Linnaeus took up the task, fully aware of its import. His epic Systema Naturae was published in twelve editions, the first being a mere 12 pages, presented in six folios. The 12th edition required two volumes totaling 1,855 pages in 927.5 folios. Its scope? All the things, arranged in three kingdoms: Regnum Animale, Regnum Vegetabile and Regnum Lapideum (Mineral).

Late in his life, the Prince of Botany, having been ennobled by King Adolf Frederick in 1757 and sporting a new name, Carl von Linné, reviewed his accomplishments; he found them good. In fact, better than good. In one of his autobiographies (there were four in total, which might tell you something) he wrote:

No one has been a greater botanist or zoologist. No one has written more books, more correctly, more methodically, from personal experience. No one has more completely changed a whole science and started a new epoch.

And you? Hopefully you have somewhat less grand an opinion of yourself, as you should, being among the lucky few with time on your hands, only to fill it in some trivial pursuit. Like golfing, collecting butterflies, reading stupid blogs. ΕΥΦΡΟΣΥΝΟΣ! (Enjoy! Knock yourself out!)

Returning to your favorite subject (yourself, here writ large, your species), Linnaeus took a number of swings at the pitch of battering that ennobled sort into taxonomic submission. As a devout Lutheran, he was convinced that the deity had created each of all the things as it appeared, in a fixed hierarchy; in no way did he anticipate Darwin’s theory of descent. Still, the Prince of Botany had a bureaucrat’s eye for similarity, as to characteristics, and developed the filing system for storage and retrieval. Which gave Darwin an important hint.

To swing one: In the first edition of Systema Naturae, published in 1735, Homo was listed in the Class Quadropedia (four footed) and Order Anthropomorpha (human-shaped). Its cell mates—taxa in the same Order—were Simia (monkeys and apes), and, somewhat surprisingly, Bradypus (sloths). Two points are worthy of note here. First, humans were included in the Prince’s zoo (Regnum Animale), which caused some considerable consternation among both scholars and theologians—but not much trouble for Linnaeus as it was the eighteenth century, not the sixteenth or seventeenth. Second, homo was not given a morphological epithet (you might expect bipedalis), but a … gnomic one: Nosce te ipsum, “know thyself” (the Latin rendition of Aristotle’s Γνῶθι σεαυτόν).

Very strange. Stranger still, the taxonomy Animale > Quadropedia > Anthropomorpha > Homo Nosce te ipsum was maintained through the ninth edition of Systema Naturae, published in 1756. The epithetical phrase stood for more than two decades! What could possibly be meant?

An elaborating footnote in the sixth edition (1748) hints at an answer, as it includes such phrases as “You are an immortal soul created in the image of God”; “You are emperor of the animals”; “If you know these things, then you are human.” Homo immortalis? Homo rex animalium? Maybe, but only if you know these things.

To swing two: The 10th edition of Systema Naturae (1758) marked a major revision. The Class Quadropedia was dropped in favor of Mammalia (suckling animals), the Order Anthropomorpha replaced by Primates (having four incisors in each jaw, two pectoral teats, and nails on digits). Homo’s cell mates were now Simia (apes and monkeys, many species listed), Lemur (lemurs, colugos) and Vespertilio (bats–all varieties of them). Sloths were demoted to the Order Bruta.

But the most significant revision was structural in nature; binomial nomenclature now rigorously employed. Which presented a problem for Homo Nosce te ipsum. The newly minted Carl von Linné must have given this a great deal of thought. How to capture in one word the intent behind the previous epithet, which reads like an imperative but whose gloss hints at a conditional (only if…)?

The first clue in this mystery is given in the listing of the ennobled species in the 10th edition:

HOMO nosce Te ipsum. (*)

Sapiens

The asterisk refers to a lengthy footnote (clue the second), which begins:

(*) Nosse Se Ipsum gradus est primus sapientiae, dictumque Solonis, quondam scriptum litteris aureis supra Dianae Templum. Mus. ADOLPH. FRID. Praefat.

(*) “To know thyself is the first step of wisdom,” a saying of Solon, once inscribed in golden letters above the Temple of Diana. Mus. ADOLPH. FRID. Preface.

Additional sleuthing reveals that the notation “Mus. ADOLPH. FRID. Praefat.” refers to the “Museum Adolphi Friderici” (Latin for “Museum of Adolphus Frederick”, the king who ennobled Carl) and specifically to the preface (“Praefatio”) of one of its published works.

Which work might it be? Prepare to be astonished.

It was the 1754 publication titled Museum S:ae R:ae M:tis Adolphi Friderici (Latin for “Museum of His Most Serene Majesty Adolf Frederick”), its preface, “Reflections on the Study of Nature”, having been penned by none other than the Prince of Botany. Wherein he wrote:

The knowledge of one’s self is the first step towards wisdom: this was the favorite precept of the wise Solon, and was written in letters of gold on the entrance of the temple of Diana.

A man surely cannot be said to have attained this self-knowledge, unless he has at least made himself acquainted with his origin, and the duties that are incumbent upon him.

Sapience was not an inherent characteristic of the species, but a possible one. Earned, not given.

In a meaningful way, then, Linnaeus ended (in the 10th edition) where he began (in the first), though in a more subtle expression. The imperative, Nosce te ipsum (“know thyself”) became an exhortation, ending in s: Sapiens, “Become capable of discerning.”

An epithet that you and yours wear to this day, concerned with discerning or otherwise (mostly the latter, thus undeserving).