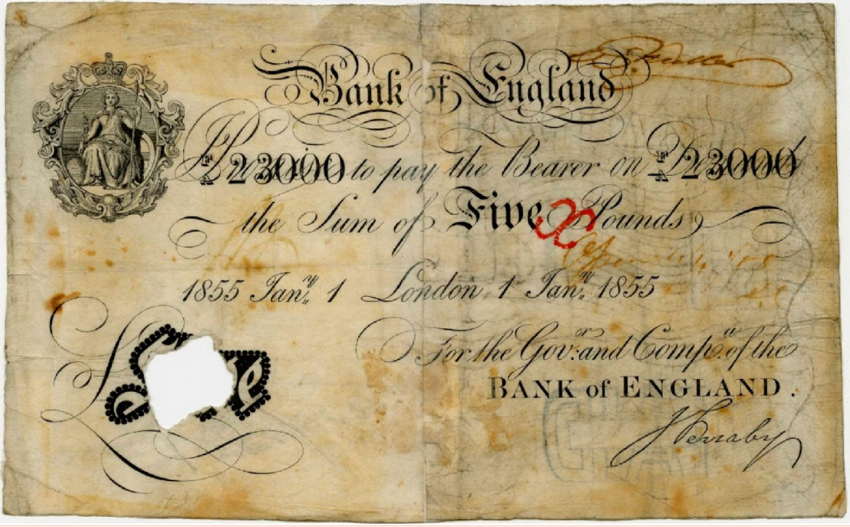

Image credit: ‘Bearer’: Courtesy of the Bank of England Museum.

PART 4 of a series

And it must follow, as the night the day

– William Shakespeare, Hamlet

One question that might be worth asking is, How did you get here? (No, no one has any interest in how poor your parenting might have been, or how poor your choices in college major, like English or Marketing or Literary Criticism…. Take that up with your therapist.)

Maybe a review of what happened (the historical version of is)?

A royal mess

You may remember (if learning is in your wheelhouse, which, little evidence to date…) that subscriptions were invented in the 17th century to fund works of literature and art that could not otherwise be produced. John Minsheu? Ring a bell?

You may further remember that this model was adopted by scholarly publications. And that worked pretty well for a very long time, disseminating scholarly knowledge to those who had want or need of it. Well, sort of…. Not.

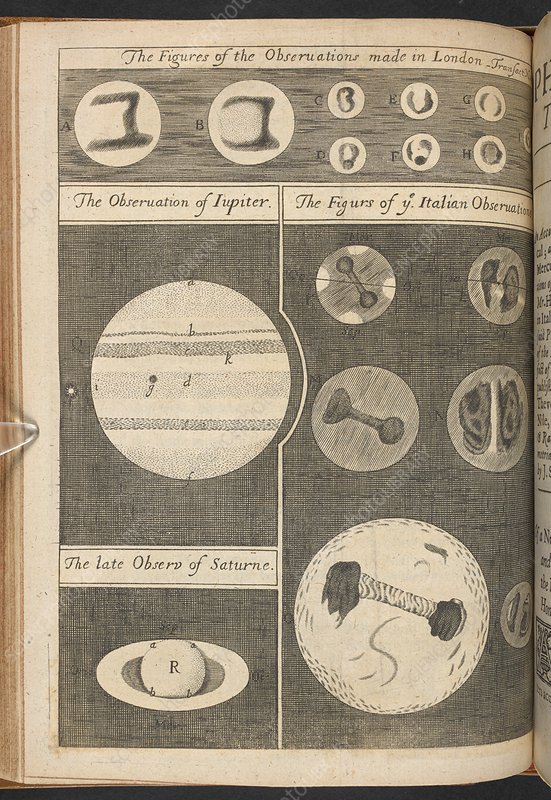

Turns out, not a lot is known about application of the subscription (assurance contract) model to periodicals in the 17th century. It was an established model for books (see Part 2), but booksellers in that period (and later) weren’t convinced that money could be made on periodicals, whatever the means of extracting it.1 The very first periodical generally considered to be a “scientific” journal, Journal des sçavans, likely had subscribers but not enough to support it. That fell to wealthy patrons.2 Oldenburg himself, before launching the Philosophical Transactions, wrote to Henry Boyle that he was thinking of creating a compliment to Journal des sçavans, consisting entirely of his contributions and financed by subscriptions, and he asked Boyle to recruit subscribers. That went nowhere.3

In short, it was a financial mess. And it remained a mess for centuries. Why?

As it turns out, philosophical scholars—however good they may be at what they do—are terrible at doing anything else. Including making their great-hearted desire to disseminate their startling advances—and polish their startling reputations—sustainable. (And managing their societies, but that’s an entirely different issue. The Dunning-Kruger effect4 and all that.) Almost all “scientific” journals failed very quickly, particularly if they lacked official sponsorships.5

Take the case of the Royal Society and its famed Philosophical Transactions. Oldenburg started it as a way to make his living. He figured that it would break even at 300 copies, but complained that at most it had managed to cover his rent.6 After Oldenburg’s death in 1677, Transactions passed through a series of editors—a position whose winning often enough involved royal battles of egos—at least one of whom financed production and distribution out of his own pocket.7 Transactions wasn’t even an official publication of the Society until 1753, but rather more functioned as a fiefdom of the ruling editor. A money losing one at that.

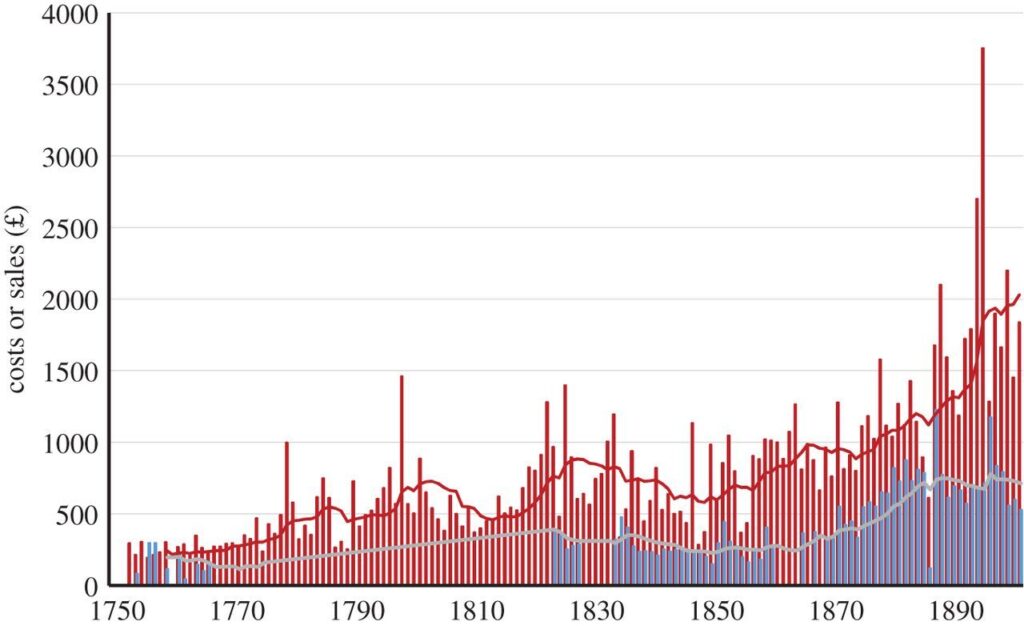

Even after wresting control from the editors, the Royal Society wasn’t interested in making a profit on its publishing activities. It understood its role to be largely philanthropic, which entailed distributing the Transactions gratis to libraries and other societies to enhance the Society’s prestige and receive publications in return. Insofar as the Society paid attention to publication costs at all,8 the apparent hope was that income earned from membership fees paid by Fellows (considered subscriptions) would cover Transactions costs. But Fellows had a habit of falling into arrears, requiring the Society to send lawyers after them to collect unpaid dues. The booksellers were also unhappy, complaining in 1766 that demand for paid copies was depressed due to copies being given freely to the Fellows.9

The situation was not unique to the Royal Society. In the mid 19th century, the printer Richard Taylor reported:

Scientific journals in this country are supported with great difficulty…. I have witnessed in my own recollection a failure of all the scientific journals almost that have been set on foot… They have all of them failed from an inability to cover their expense.10

For the Royal Society, it was a royal mess and a growing one. Earnings from the Society’s investment portfolio was a help when Society finances as a whole hit a rough spot. Wealthy Fellows could be asked for donations. But by the end of the 19th century, the battle between ought (mission) with is (finances) fell to the latter, and the Society went hat in hand to the British government for a subsidy. The success of their appeal, which resulted in a government subsidy into the 20th century, allowed the Society “to avoid a root-and-branch rethinking of its publishing activities.”11

Some might call that success. Others might characterize it differently.

Dextrarum iunctio

Here’s the thing about wars: they’re great for science, both in its acceleration and in its funding. WW I was good. WWII was great.

Before WWII, the US government played a very limited role in funding academic research. Industry carried much of the load. To take an extreme case, by 1929 one-third of MIT’s faculty were doing research for a corporate sponsor. “What sort of work? Faculty members found it difficult to say, because many of their arrangements forbade publication of results without the sponsor’s approval.”12

Can you say excludable? And why might it be excluded…?

But then something bad happened: the market crashed. MIT’s annual budget plummeted, some departments by as much as 60% in four years.13 Other universities weren’t as reliant on corporate cash for research, but like every other sector of the economy, institutions of higher education were in trouble. WWII couldn’t come fast enough.

In 1941, Franklin Roosevelt created the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) by executive order. Its remit was to assure “adequate provision for research on scientific and medical problems relating to the national defense.”14 Led by Vannevar Bush, an engineer who had left MIT to become the president of the Carnegie Institution, the government began to fund scientific research in an unprecedented way. The OSRD might have hired or drafted its own researchers, but for the most part chose a different path, funneling much of its money to academic institutions. Thousands of research contracts were issued. By 1945, over 90% of MIT’s annual budget was funded by federal research contracts.15

Following the war, Bush authored a bold vision for public funding of scientific research in his famous report to Roosevelt, Science: the endless frontier. It provided the central argument for government funding of scientific research conducted (without political interference) within the academy:

If the colleges, universities, and research institutes are to meet the rapidly increasing demands of industry and Government for new scientific knowledge, their basic research should be strengthened by use of public funds.16

From there it was off to the races. Bush’s report was the model for the creation of the National Science Foundation in 1950, which itself served as a model for other US agencies involved in scientific research.17 US federal funding grew from $3.5 billion in 1955 to $137.8 billion in 2020, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.3%.18

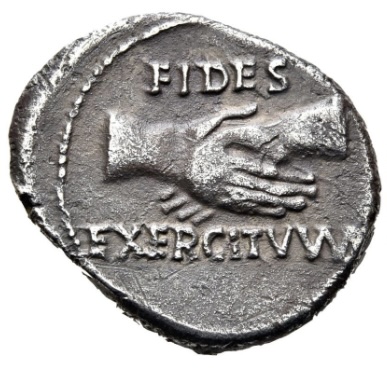

As with the Royal Society, a government handout was needed—and the academy was happy to grasp it. A mutually beneficial handshake.

Ham-fisted

What the US government had done, however intentionally, was to create a market for research outputs, chiefly journal articles. Other countries, imitating the US in building their own science capacity, joined in, enlarging the market. Flooded with cash, the academy grew their departments and libraries both.

So many new philosophical scholars to commence scribbling so many jots to be published in so many journals to be purchased by so many libraries. What could possibly go wrong?

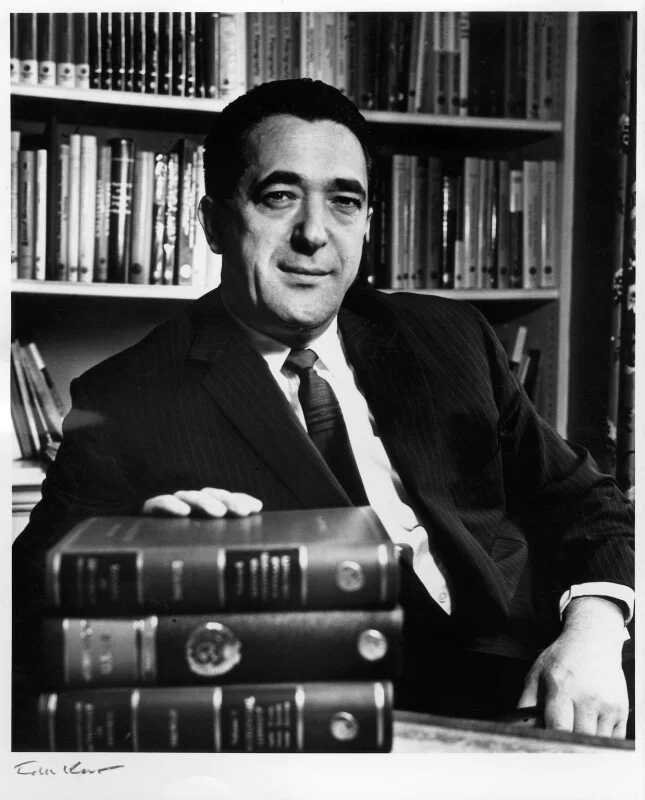

As night follows the day, these developments did not go unnoticed. Particularly by one individual: Robert Maxwell (hereafter HWSNBN). He came to see the market opportunity government funding presented; he also saw who didn’t. And who might that have been? The philosophical scholars running academic societies, of course.

As mentioned above, the philosophers had been very poor publishers for quite some time, due to their ideological commitment to philanthropic dissemination over solvency. They couldn’t parse a P&L to save their lives, if they had any interest in trying. Which they didn’t. Around 1946, for example, “the British Chemical Society had a months-long backlog of articles for publication, and relied on cash handouts from the Royal Society to run its printing operations.”19 Said cash handouts being ultimately bankrolled by the British taxpayer.

In post-war Britain, the government felt the need to take things in hand. British science was excellent, but its publishing operations left more than a little to be desired. It selected Butterworths, a well respected British book publisher focused primarily on law books, to merge with the German science publishing juggernaut Springer Verlag. The timing seemed perfect. Butterworths could learn from Springer’s expertise in scientific publishing, and Springer was at the time not allowed to sell books outside of Germany (a post-war prohibition). A merger would solve a multitude of problems.

Enter HWSNBN, who had business dealings with Springer, including acting as director of the British company, Springer Publishing Company Ltd., and another British company that played a minor role in corralling the right people to meet the right people to make something happen. After a series of negotiations, two new legal entities were formed: Butterworth-Springer Ltd. and Lange, Maxwell and Springer Ltd. The latter was the exclusive agent for sales of Springer publications outside of Germany as well as having rights to sell Butterworth-Springer publications in many (but not all) global regions.

Sound complicated? It was. Sound workable? It wasn’t.

By 1951, Butterworths concluded that it was getting the short end of the stick. It sold its shares in Butterworth-Springer Ltd. for £13,000 (about £337,995 in today’s pounds) to HWSNBN and waived a debt of £23,547 owed by Butterworth-Springer Ltd. to Butterworths. “In effect, therefore, Butterworths wrote off £10,547 [£274,217] on its adventure with Maxwell and Springer.”20 It was a fire sale.

For its part, Butterworths—apparently obsessed with the prospect of making money in the science publishing market—pressed on separately. It published 14 scientific books between 1948 and 1950 as well as two journals, Research and Fuel.21 Both efforts were financial failures.

Odd thing is, HWSNBN knew little to nothing about publishing. He was more of a distributor and marketer. And he had as little interest in, initially, as knowledge of publishing. His intent had been to sell his shares in Butterworth-Springer to Springer, but when Springer didn’t bite, HWSNBN was forced to raise cash to buy Springer’s shares as well. What to do?

Enter a gentle soul with a spine of steel. Paul Rosbaud was an Austrian physicist and metallurgist. Before the war, rather than continuing his research, Rosbaud accepted a job at the German journal Metallwirtschaft to recruit contributions from authors, “a roving scientific talent scout.”21

In 1932, Springer, whose journal sales were said to be “larger than the combined total of the remaining world’s scientific publishers,”22 hired Rosbaud to play a similar role for the journal Naturwissenschaften.

When the war came, Rosbaud, after moving his family to Britain (his wife was Jewish), returned to his work in Germany—and became a British spy.23 Not the safest role one might play. He never spoke of his experiences during that time. Knowledge not divulged.

After the war, Rosbaud found himself “trapped in Berlin and in danger from the Russians, who tried to kidnap him.”24 He was secreted out with the help of British intelligence and, due to another physicist with connections to MI6, landed at Buttersworth. That was the point of intersection between HWSNBN and Rosbaud.

Having little interest in his accidental purchase of Butterworth-Springer, HWSNBN recruited Rosbaud to run it. At first reluctant, due to his dim view of HWSNBN, Rosbaud ultimately accepted the position. It was not a match made in heaven:

Throughout history, ill-matched pairs of men have found themselves yoked together by fate, sometimes in willing collaboration, sometimes in prolonged opposition. Some examples: Pitt and Fox; Darwin and Wilberforce; Eddington and Chandrasekhar. The two men who provide my theme, Paul Rosbaud and [HWSNBN], were more disparate than any of these pairs.25

It was Rosbaud, not HWSNBN, who rebranded Butterworth-Springer as Pergamon Press, choosing its colophon based on a gold coin featuring the head of Athena on the obverse, minted in Pergamon.26 The new entity inherited Butterworth-Springer’s book title list as well as three of its journals.

It was also Rosbaud, not HWSNBN, who first saw the opportunity presented by the post-war cash governments were pumping into science. He worked his network, recruiting scientists to create new journals in emerging fields—not for the love of money, but for the love of science. Rosbaud had little interest in money, and as if to prove it, died nearly penniless.

HWSNBN had a different goal altogether: becoming a millionaire. His focus between 1951 and 1954 was directing the book-selling company Simpkin Marshall, which he had purchased. And which he managed to drive into bankruptcy. It was then, and only then, that he remembered that he had also ended up owning Pergamon Press. Having learned from Rosbaud that the time was ripe to launch new journals—as well as how to do it (personal contacts)—HWSNBN got to work, throwing parties for scientists, playing upon their vanity (through charm or bullying) to bend them to his will.

It was an extraordinarily, almost unimaginably, lucrative strategy. What HWSNBN noticed, perhaps uniquely, was that the market (libraries) was captive and the funding source (governments) apparently inexhaustible—creating an insanely profitable opportunity.

Why did the British government stick its ham fist into this? Partly it was due to a genuine concern to raise Britains’ scientific publishing capacity to the level of its scientific and technological excellence. But it was also motivated by a desire, “shared by all the London parties,”27 to keep Springer out of the hands of the Yanks.

It may also have been due to the fact that after the war, Britain was broke. It had nothing like the cash the US had to throw at science, so it sought a public-private partnership, much like Coase’s lighthouses turned out actually to be (contrary to Coase’s libertarian telling of the tale; see Part 3).

MENTAL HEALTH BREAK

Time for a quick mental health break.28

The British governments plan to fix Britain’s underperforming scientific publishing operations involved the assembly of a Scientific Advisory Board. It was replete with scientific luminaries, many of them knighted. Among them were Sir Alexander Fleming, who had discovered penicillin, and Sir Edward Appleton, a pioneer in radiophysics and winner of the Nobel Prize in 1947. It was also replete with MI6 spooks.

Chief among the spooks was someone named Count Frederick Vanden Heuvel, who had been the MI6 station chief in Berne, Switzerland, during the Second World War. He was, and remains, a shadowy figure. His friends knew him as “Fanny” or “Van.” To others he was known as “Fanny the Fixer.”

Fanny’s title came by virtue of having been the son of a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, a title Fanny inherited. Did you know there were such things as papal counts?

Indeed so. Until the 19th century, the Pope was the sovereign ruler of the Papal States, comprising a number of territories on the Apennine Peninsula. That came with the right to bestow titles and, before 1870 (when Italy was unified), territorial rights.

Vanden Hovel continued his work for MI6 during the Cold War, running a MI6 network codenamed “BIN.” His code number was Z-1, a reference to BIN’s history in another shadowy group known as the Z Organisation, a network of British businessmen who gathered intelligence before and during the war.

Among BIN’s activities was the recruitment of a network of journalists in Britain’s newspaper industry. It had three main functions:

- to arrange journalistic cover for MI6 agents traveling in the Soviet sphere,

- to recruit actual journalists to gather intelligence, and

- to encourage journalists to write pro-British propaganda.

The Venn diagram overlaps with HWSNBN and Rosbaud were significant, as both had worked for British intelligence and both were in the publishing business.

Who was Who records Vanden Heuvel’s death in 1963 at the age of 78.

Jefferson’s taper re-redux

What might you have learned through this overlong tour of the historical is? If you’re at all interested in learning, rather than hurling assertions back and forth….

Maybe that tapers have never been free?

Maybe that in the US, the government invented the current financial model, quite happy to burn both ends of the candle against the middle, with taxpayers footing the bill?

Maybe that HWSNBN was not the party initially responsible for recognizing the market opportunity and catalyzing the growth in the number of journals, but someone interested solely in the advancement of science?

Maybe that both of you (blue and red jersey wearers alike) benefited from the business side of war handsomely? Lucky you.

HWSNBN died in 1991, but the lesson he had learned from Rosbaud didn’t die with him. His business model worked well. Like, beyond expectation well. Using the Scopus index as indicative of a wider trend, the number of journals published grew from 2,365 in 1955 to 24,147 in 2020, a CAGR of 3.6%.29

Unsavory a character as HWSNBN may have been (ur … was), this tale’s real villain or genius (depending, no doubt, on the color of the jersey you’re wearing) has not yet been named. That would be Pierre Vinken, the CEO and Chairman of Elsevier from 1972 to 1995. In a scathing piece in The Guardian, Stephen Buranyi relates a telling interview:

At the time of the merger, Charkin, the former Macmillan CEO, recalls advising Pierre Vinken, the CEO of Elsevier, that Pergamon was a mature business, and that Elsevier had overpaid for it. But Vinken had no doubts, Charkin recalled: “He said, ‘You have no idea how profitable these journals are once you stop doing anything. When you’re building a journal, you spend time getting good editorial boards, you treat them well, you give them dinners. Then you market the thing and your salespeople go out there to sell subscriptions, which is slow and tough, and you try to make the journal as good as possible. That’s what happened at Pergamon. And then we buy it and we stop doing all that stuff and then the cash just pours out and you wouldn’t believe how wonderful it is.’ He was right and I was wrong.”30

Three years after the purchase, Vinken raised the prices of its journals by 50%. Tapers had become very expensive.

Epilogue

HWSNBN had profited handsomely from Pergamon Press, as, thanks to Uncle Sam, it was a taxpayer funded cash cow. But he was insatiable in his appetites and used that cash to make any number of dodgy investments, which didn’t do nearly as well. By a long shot. He was forced him to sell Pergamon to Elsevier in 1991 to cover debts (as well as stealing $1.2 billion from the pension funds of his various business concerns).31

If it’s any consolation to the blue team, HWSNBN met a grisly end. One evening in November 1991, HWSNBN had a contentious call with his son Kevin. They were due to have a meeting with the Bank of England concerning HWSNBN’s default on £50 million in loans, and Kevin wanted to prepare. At the time, HWSNBN was cruising on his yacht, the Lady Ghislaine,32 to the Canary Islands. Kevin called the captain of the yacht the next morning to pick up the conversation, only to be told HWSNBN was missing. Hours later, his nude body was recovered in the Atlantic Ocean. He was 68 years old.

- David Kronick, “Scientific Journal Publication in the Eighteenth Century.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 59 (1965), 34. https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.59.1.24300769. ↩︎

- Ibid., 35–36, quoting B.T. Morgan, Histoire du Journal des Sçavans (Paris: 1929), 96. ↩︎

- The Correspondence of Henry Oldenburg: Vol.II 1663-1665 (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1966), 209-10. ↩︎

- It’s a thing. Look it up. ↩︎

- Between 1665 and 1790, the failure rate was 60%, with only 10% surviving 25 years or more. See Kronic, op. cit., 34. ↩︎

- Correspondence, op. cit., 646-47. ↩︎

- Hans Sloane. See A. Fyfe et al., “350 Years of Scientific Periodicals,” Notes and Records: the Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 69 (2015), 230. ↩︎

- The Society’s Finance Committee met occasionally starting in the 1830s and was not a standing committee until the end of the century. Further, the Society’s accounts did not have a P&L for publications until the 20th century. See Aileen Fyfe, “Journals, learned societies and money: Philosophical Transactions, ca. 1750–1900,” Notes and Records: Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 69 (2015), 278-80. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2015.0032. ↩︎

- Ibid., 287. ↩︎

- Report of the Select Committee on Postage (1837-38), quoted in ibid., 277. ↩︎

- Ibid., 291. ↩︎

- David Kaiser, “The search for clean cash,” Nature 472 (April 2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/472030a. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Executive Order 8807—Establishing the Office of Scientific Research and Development in the Executive Office of the President and Defining Its Functions and Duties,” The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-8807-establishing-the-office-scientific-research-and-development-the ↩︎

- Kaiser, op. cit. ↩︎

- Vannevar Bush, “Science, the endless frontier: A report to the President,” United States Government Printing Office (Washington, DC: 1945), 20. ↩︎

- Mark W. Neff, “How Academic Science Gave Its Soul to the Publishing Industry,” Issues in Science and Technology 26, no. 2 (Winter 2020). https://issues.org/how-academic-science-gave-its-soul-to-the-publishing-industry/.

↩︎ - “U.S. Research and Development Funding and Performance: Fact Sheet,” Congressional Research Service (September 2022), 2. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44307.pdf. ↩︎

- Stephen Buranyi, “Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science?” The Guardian, June 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science.

↩︎ - H. Kay Jones, Butterworths: History of a Publishing House, 2nd edition. (London: Butterworths, 1997), 111. See pp. 108–112 for the entire saga. ↩︎

- Research was launched by Butterworths in 1947; Fuel was purchased from a certain Dr. Lessing. See Jones, op. cit. ↩︎

- Chan op. cit., 1994, 38. ↩︎

- Robert W. Chan, “The origins of Pergamon Press: Rosbaud and Maxwell,” European Review 2, no. 1 (1994), 37. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-review/article/abs/origins-of-pergamon-press-rosbaud-and-maxwell/17DA853EC76BF5BEA948B21089C321E1.

↩︎ - Chan op. cit., 1994, 38. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Pergamon was a Roman city in Asia Minor )modern Turkey). It has been excavated by the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut for well over a century.

↩︎ - Jones, op. cit., 110. ↩︎

- Details in the following are drawn from Jones, op. cit., 108-09; “Special Bulletin: The Letter from Geneva,” Coldspur, April 23, 2020, https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-the-letter-from-geneva/; “I. The London Station,” Jeremy Duns, https://www.jeremy-duns.com/agent/1; and Keith Jeffery, The Secret History of MI6 (New York, Penguin Books, 2011), Kindle edition. ↩︎

- Data from Mike Thelwall and Pardeep Sud, “Scopes 1900-2020: Growth in articles, abstracts, countries, fields, and journals,” Quantitative Science Studies 3, no. 1 (April 2022). https://direct.mit.edu/qss/article/3/1/37/109076/Scopus-1900-2020-Growth-in-articles-abstracts.

↩︎ - Buranyi, op. cit.

↩︎ - “Robert Maxwell,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Maxwell. ↩︎

- HWSNBN’s daughter Ghislaine is currently serving a 20 year sentence in federal prison for participating in a years-long scheme with her longtime confidante Jeffrey Epstein to groom and sexually abuse underage girls. ↩︎