Image credit: Pieter Claesz, Still Life with a Lighted Candle, 1627 (Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis The Hague)

PART 1 OF A SERIES

If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea…. Its peculiar character … is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening mine.

– Thomas Jefferson, letter to Isaac McPherson, 1813

Many things in life are tiresome, and among those things might fairly be included the open-access debate in scholarly publishing. It has all the attributes of tiresomeness: ideological fervor, entrenched positions, endless duration, and a lack of definition of just what is being debated.

This series will do nothing to resolve the first two of those attributes, adds to the third, but may be of some help in resolving the fourth.

You may be the type of person more persuaded by oughts and shoulds, prone to quote Jefferson (see above) when striving for the ideal of making the outputs of scholarly research freely available to all. If so, you would be in company, as this is a common trope among those wearing your jersey. Say it’s a blue jersey.

Or you may be the type of person who, when hearing Jefferson so quoted (again… you think), sighs and asks, But who’s going to pay for the candles? You may agree that scholarly knowledge should be widely available—as widely as possible—but the perfect is often the enemy of the good. You and those sharing your fatigue also wear a jersey. Say it’s a red jersey.

By some perverse accident of history, you—whichever sort of you—find yourself a member of a team and participating in a tiresome debate (to put it kindly) that resembles nothing more than trench warfare, with its frozen lines, lots of mud and fog.

Can anything better be done? Maybe an attempt to find some common ground first, and go from there?

What we talk about when we talk about good

It’s typically a good (if tedious) idea to start with defining terms.

Is knowledge good in some vague, general way—a good thing? By and large everyone likely agrees that it is—at least in sufficient quantity, a little of it being, as is said, a dangerous thing.

Is scholarly information a form of knowledge? Again, yes. Certainly. And so! An easy syllogism and an area of agreement:

- All knowledge is a good thing.

- Scholarly information is a form of knowledge.

- Therefore, scholarly information is a good thing.

Whew! Glad that’s done—everyone agrees! Maybe you should leave well enough alone and do something more useful, like hitting the links.

Except, maybe it’s complicated….

Is knowledge a social good? This is a little more tricky, as the question wades into the murky waters of moral philosophy.

The classic Utilitarian definition of common good is “the greatest possible good for the greatest number of people.” Examples include access to clean air and water, literacy, education, and, for some, access to healthcare. It’s a safe bet that no one would maintain that clean air, clean water, or literacy—leave alone healthcare—are in fact universally accessible.

These are ideals, in a moral sense, and people tend to speak of them in subjunctive shoulds and woulds: “They should be universally enjoyed.” “Would that they were.”

Still, it’s also a safe bet that people of good will (including, no doubt, you) might affirm that, as an ideal, knowledge should be a common good, and societies should strive to make it so. And further, scholarly knowledge, as a subset of knowledge, should be included in that ideal.

But a statement of preference does not make something so. To say something ought to be is to say nothing of what is.

Perhaps, put the horse before the cart (for once) and focus on is before jumping to oughts? If, as a good and generous person (which you undoubtedly are) you want to increase access to scholarly knowledge, it might be a good idea to know what it is, what might be necessary to achieve your ideal—and how to pay for it.

Fortunately, economists tend to be a cold-blooded group, generally fond of precise definitions and somewhat less prone to oughtism and descent into ideological bickering than the jersey-wearing camps in the open-access debate. When they use the word “good” they rigorously stick to its use attributively, as a noun. A good is a thing with utility, a useful thing.

And goods have attributes by which they can be distinguished:

- rivalrous (in consumption)

- excludable (from consumption)

Rivalrous means that one person’s consumption of a good diminishes another’s. Your eating the loaf of bread prevents others from consuming it. Conversely, your consumption of the electromagnetic spectrum in the form of visible light in no way reduces anyone else’s; light is non-rivalrous in consumption.

Excludable refers to the degree in which a good can be limited to only those who pay for it. Your clothes are excludable (though you may chose to share that sweater with someone else, so long as you’re not wearing it). Conversely, non-excludable means that it is impossible, in practical terms, to limit consumption of the good. You cannot practically exclude the electromagnetic spectrum from others—even your bitterest enemies.

So happily, economists have provided you with a clear set of characteristics by which to distinguish one type of good from another.

| Type | Rivalrous | Excludable |

|---|---|---|

| Public good | ✗ | ✗ |

| Common good | ✔ | ✗ |

| Club good | ✗ | ✔ |

| Private good | ✔ | ✔ |

Now your job (both of you, as your agreed goal is to find some common ground) is to identify which type of good thing scholarly knowledge might be.

Of philosophers and thieves

In the 17th century, scientists were genuinely concerned with what they termed philosophical robbery, what you would now call intellectual property theft. They felt a real concern to establish the priority of observation, discovery, or experimental results, and went to extraordinary lengths to do so, including the use of anagrams.

Before formal publication in books—a long and expensive process in the 17th century—a sentence announcing a discovery would be encrypted into an anagram and deposited with an official witness or circulated. If a competitor claimed the same discovery, the original scientist could then refer to their witness to unscramble the anagram and establish their priority.

In July 1610, Galileo sent a letter to his patron, Giuliano de’ Medici, expressing his concern for secrecy:

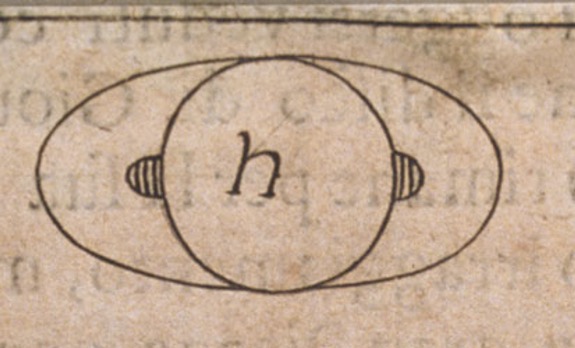

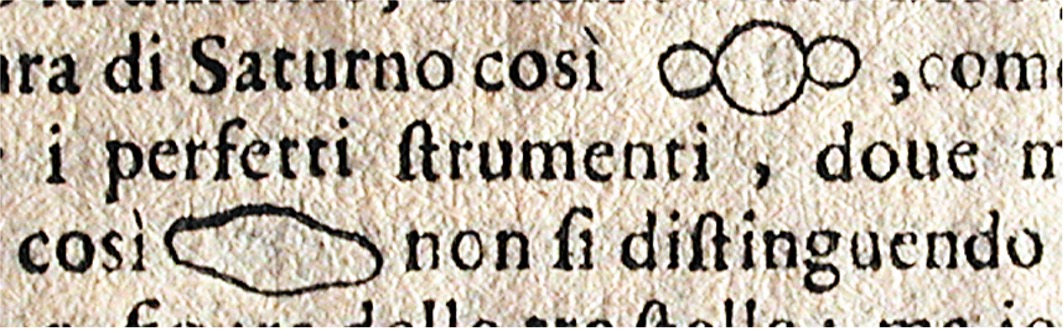

I discovered another very strange wonder, which I should like to make known to their Highnesses…, keeping it secret, however, until the time when my work is published … the star of Saturn is not a single star, but is a composite of three, which almost touch each other, never change or move relative to each other, and are arranged in a row along the zodiac, the middle one being three times larger than the lateral ones, and they are situated in this form: oOo.1

And here is the Latin anagram that Galileo sent to Kepler in 1610, announcing that he had made an important observation and thereby establishing Galileo’s pride of place.

| Galileo’s anagram | smaismrmilmepoetaleumibunenugttauiras |

| Unscrambled | altissimum planetam tergeminum observari |

| Translation | I have observed the uppermost planet triple. |

The image to the left is a detail from a plate in The Assayer, which Galileo published in 1623, showing Galileo’s view—through a 20-power telescope—of “the uppermost planet triple.”

Breaking the culture of secrecy in which science operated in order to allow dissemination of knowledge was one of the most serious challenges the Royal Society faced in the 17th century.

Henry Oldenburg, the first secretary of the Royal Society, wrote to Robert Boyle (generally regarded as the first chemist) on the subject in 1664. The letter shows the critical role the Society played in providing a mechanism for registration of priority under the authority of the Society, precisely in order to break the culture of secrecy and facilitate broad dissemination. Oldenburg was reporting to Boyle on a meeting of the Society, at which the results of an experiment had been presented:

This account was lately undertaken under the consideration of the Society, and, when it was spoken of at their meeting, order was given, yt it should be punctually registred at ye same time, when it was first mentioned, to ye end, yt Mr Huygens might have his due, and yt his inventions be recorded for his honor to posterity, as well as the inventions the ye English Virtuosi. This justice and generosity of our Society is exceedingly commendable, and does rejoyce me, as often as I think on’t, chiefly upon this account, yt I thence persuade myselfe, yt all Ingenious men will be thereby incouraged to impart their knowledge and discoveryes, as farre as they may, not doubting of ye Observance of ye Ole Law, of Suum cuique tribuere [“allowing to each man his own”].2

It was the inherent rivalrous and excludable nature of knowledge that the Royal Society had to overcome. Dissemination of research, considered fundamental to the progress of science, could not be routinely achieved until the author of the new knowledge (be it an observation, experiment or invention) received due credit (rivalrous) and agreed to make their work widely know (excludable).

Mental health break

Quite a lot to digest already. Time for a quick mental health break.

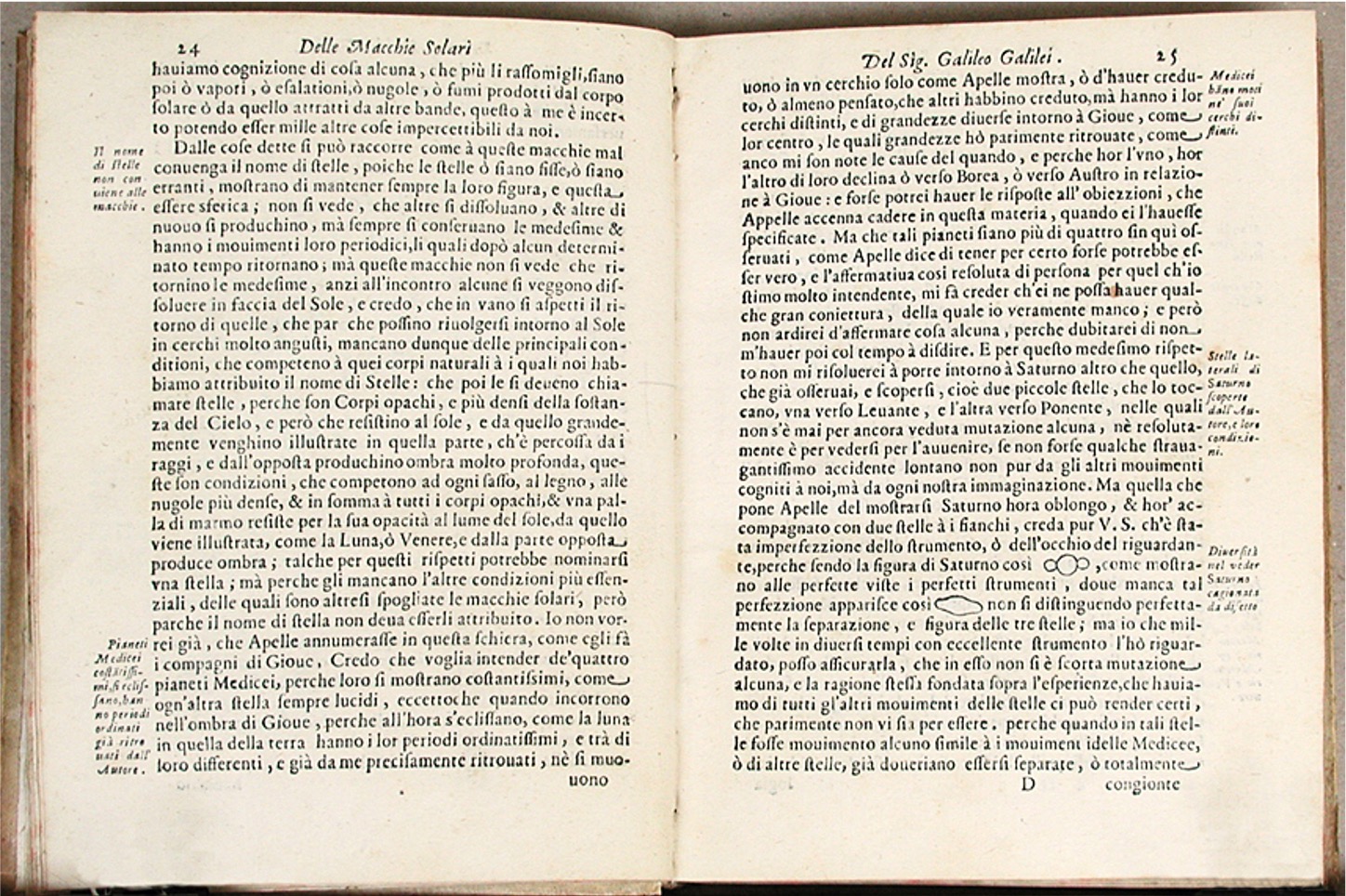

Following is a spread from Galileo’s History and Demonstrations Concerning Sunspots and Their Properties, published in 1613. Isn’t that an amazing design?

Notice how the gutters (the interior margins) are narrower than the thumbs (exterior margins), and how there’s more space at the tail (bottom margin) than the head (top margin)? And the marginalia in the thumbs?

Spreads were designed to be recognized by the eye as a single unit.

Here’s a detail of the recto from that spread:

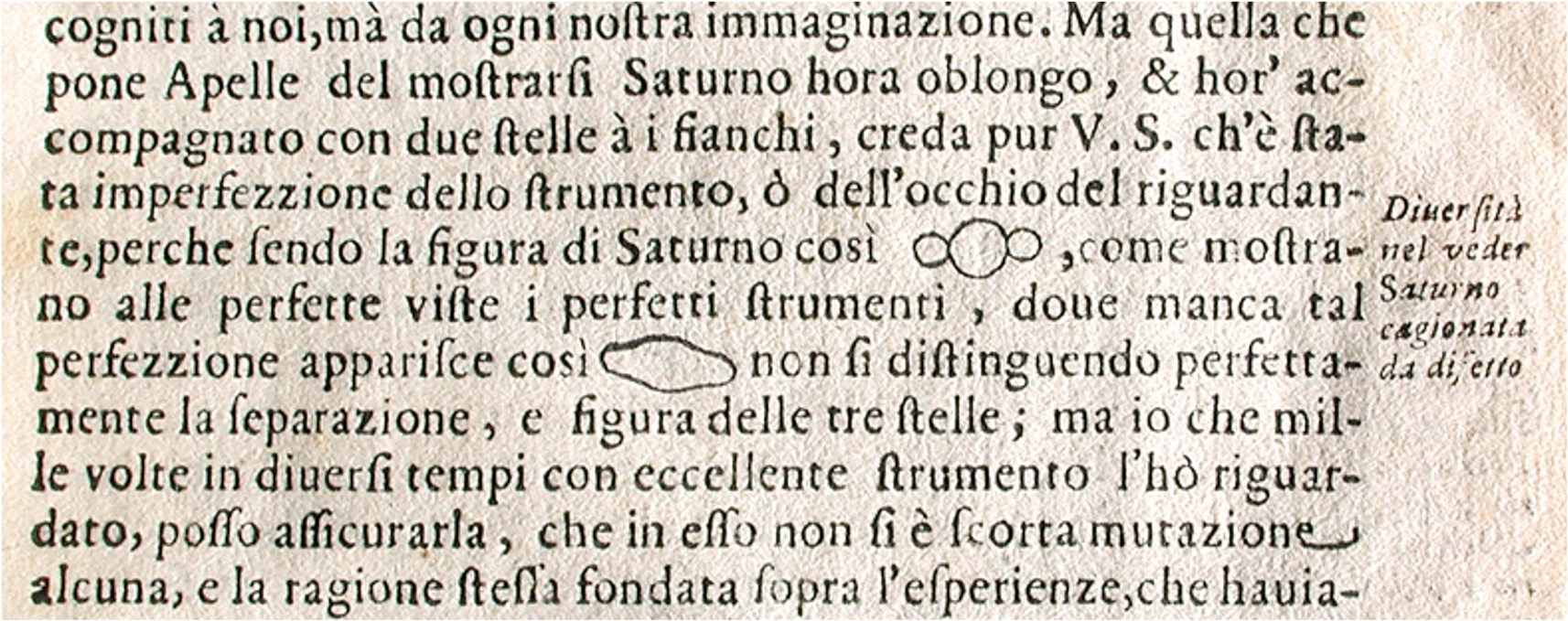

And pulling in a bit tighter:

According to Edward Tuftee, who has been called the Galileo of information graphics, the two images of Saturn were almost certainly printed right along with the type, probably carved in relief on small woodblocks, although possibly cut in lead.

Notice the beautiful ligatures (st, si)?

Doesn’t this just make you hate electricity?

Jefferson and his taper

“He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening mine.”

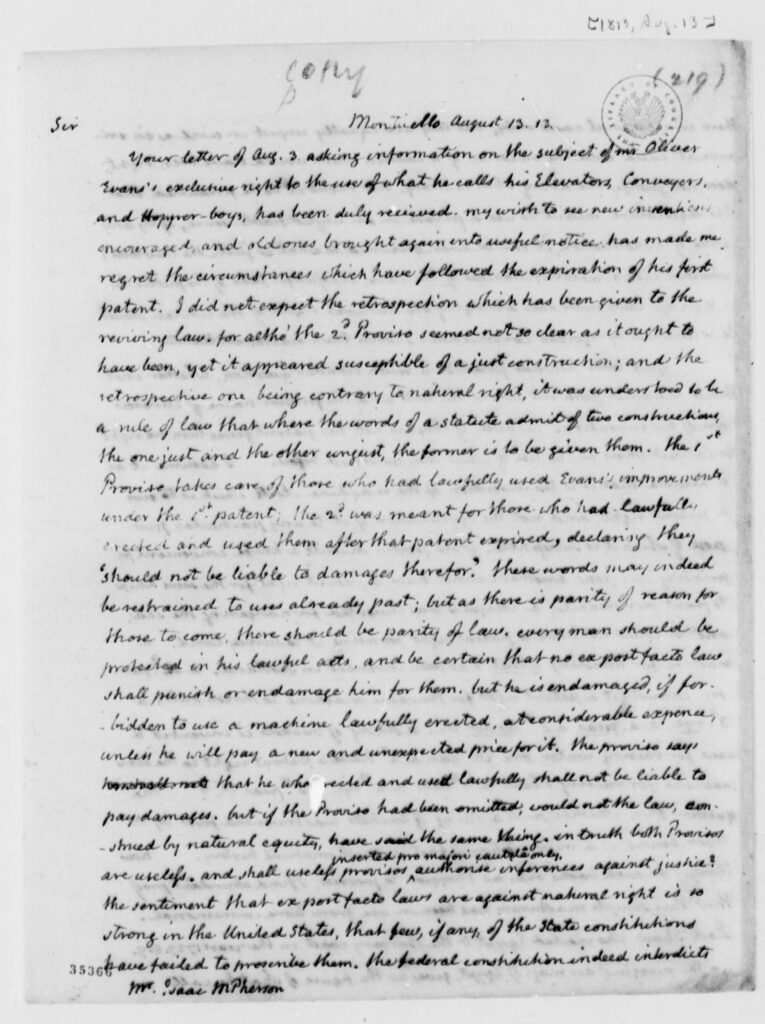

It may be reasonable to ask if those of you who quote that metaphor (typically the blue team) have read any more of Jefferson’s letter to Isaac McPherson than that pregnant sentence. (The first page of the letter is shown to the left.)3

It may further be reasonable to infer that you haven’t, as if you had, the open-access debate might have become somewhat more nuanced.

The letter was in response to McPherson’s specific query regarding the expiration of a patent granted to a Mr. Evans for milling machinery. After giving McPherson a long and detailed opinion on the point at issue, Jefferson widened the discussion. Is there any natural right to property of any sort, including inventions, land and ideas?

Jefferson was more than skeptical. Property rights are not a natural right (is), but a right granted by societies (ought), and only recently.

It has been pretended by some (and in England especially) that inventors have a natural and exclusive right to their inventions; & not merely for their own lives, but inheritable to their heirs. but while it is a moot question whether the origin of any kind of property is derived from nature at all, it would be singular to admit a natural, and even an hereditary right to inventions. it is agreed by those who have seriously considered the subject, that no individual has, of natural right, a separate property in an acre of land, for instance. by an universal law indeed, whatever, whether fixed or moveable, belongs to all men equally and in common, is the property, for the moment, of him who occupies it; but when he relinquishes the occupation the property goes with it. stable ownership is the gift of social law, and is given late in the progress of society.4

And in defining the ought, societies had to balance practical concerns against natural rights. Jefferson himself, as a member of the U.S. Patent Board for several years, had confronted this confound:

Considering the exclusive right to invention as given not of natural right, but for the benefit of society, I know well the difficulty of drawing a line between the things which are worth to the public the embarrasment of an exclusive patent, and those which are not.

That formed the context in which Jefferson offered his thoughts on ideas. “[I]f nature has made any one thing less susceptible, than all others, of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an Idea….”

At this the blue team cheers (apparently adopting Jefferson’s philosophical position on natural rights). The red team hangs fire, remembering that the very next phrase is “…which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself.”

Jefferson recognized that knowledge is excludable. How could he not? Throughout history and even now knowledge has been and is reserved: by priestly and political elites, secret societies, corporations—on and on. You may remember the strange dream you had last night and never tell anyone of it.

But—and for Jefferson it’s a big but— “…the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the reciever cannot dispossess himself of it.”

Jefferson then goes on to compare revealed ideas—public knowledge—to fire’s light, or the air we breathe and through which we move:

[T]hat ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benvolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point; and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement, or exclusive appropriation.

Setting aside the fact that Jefferson got the physics wrong5 (and said any number of things, some of them quite troubling…), he seems to have forgotten a few important things about how knowledge might be revealed, including the knowledge he was divulging to McPherson: someone had to teach him to read and write, he had to buy the paper and ink he used to write the letter, he had to buy his taper and he likely had to hire the courier to convey it from Monticello to McPherson in Alexandria, some 112 miles away.

He also overlooked the fact that knowledge is often deliberately excluded because it is rivalrous—precisely the problem Oldenburg was tackling in 1664. Knowledge is often said to be power, and power has great utility on this planet. “A wise man is strong; yea, a man of knowledge increaseth strength.”6

Knowledge in the dock

So to wrap up this portion of the inquiry (and here the Blue and Red teams both exhale in relief), how is knowledge in general (and scholarly knowledge as a subset) to be scored in the economic matrix of goods?

To review:

| Type | Rivalrous | Excludable |

|---|---|---|

| Public good | ✗ | ✗ |

| Common good | ✔ | ✗ |

| Club good | ✗ | ✔ |

| Private good | ✔ | ✔ |

Is knowledge excludable? Yes, both teams agree; even Jefferson acknowledges that point (an idea not yet divulged).

Is knowledge rivalrous? To be fair to Jefferson, no, not in the sense that one person’s mental possession of an idea or concept does not diminish someone else’s understanding of the same. But that fails to recognize the obvious reality that knowledge can be and often is a secret whose value is in the reserving. It might be a nation’s nuclear secrets, it might be a researcher’s yet-to-be published hypothesis, it might be that strange dream you had last night.

So how is scholarly knowledge to be scored in the matrix? That has much to do with the cost of Jefferson’s taper.

- The Galileo Project, Office of the Vice President of Computing of Rice University. http://galileo.rice.edu/sci/observations/saturn.html ↩︎

- The Correspondence of Henry Oldenburg: Vol.II 1663-1665 (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1966) 327-9. ↩︎

- “Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson, 13 August 1813,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0322. ↩︎

- Ibid., emphasis added. ↩︎

- Light, having no mass, does not have density. It does have intensity (which may be what Jefferson meant), but its intensity can be diminished as particles in the atmosphere absorb it. ↩︎

- Proverbs 24:5, King James Version. ↩︎