Image credit: Shirley Thompson, “Storm & Lighthouse”, The Hockley Gallery

PART 3 of a series

If all the economists were laid end to end, they would not reach a conclusion.

– George Bernard Shaw

When it comes to the provision of public goods, it turns out, fairness (suum cuique tribuere),1 has nothing to do with it. (Would that it did…). Or so classical (and neo-classical) economics has opined. It’s about is, not ought. What can happen, not what you may think should happen.

Which, if you care to think about it a bit, is the usual course of things. You know, Adam Smith, the invisible hand of the market, Calvin’s determinism.2 All that.

The inexorable nature of things, which you may embrace or abhor. Your choice (if you have a choice, which you likely don’t).

Except … you’re going to die. Likely not your choice, but there you are. Musts tend to overcome oughts.

Needs must

The building and maintenance of lighthouses has been a topic of discussion among economists since the 19th century, from John Stuary Mill’s Principles of Political Economy, published in 1848, through the present. The reason for this is that lighthouses present an archetypal instance of a pure public good, a useful model for theoretical discussion.3 Their social value is unarguable, and they fit the attributes of pure public goods (which you’ll no doubt remember from Parts 1 and 2): non-rivalrous in consumption (one’s ships use of the information provided by a lighthouse about the coast or sub-surface hazards does not diminish another ship’s use of the same information) and non-excludable (you can’t limit the light they emit to only paying consumers).

To quote Mill,

[I]t is the proper office of government to build and maintain lighthouses, establish buoys, etc. for the security of navigation: for since it is impossible that the ships at sea which are benefited by a lighthouse, should be made to pay a toll on the occasion of its use, no one would build lighthouses from motives of personal interest, unless indemnified and rewarded from a compulsory levy made by the state.4

Because the light from lighthouses is inherently (as a practical matter) non-excludable, thus un-productizable, economic theorists were in general agreement for two centuries that it fell to governments to provide this public good (and goods with similar characteristics) and to pay for their provision through general taxation.

In short, the only way to overcome the free-rider problem lighthouses present was by compulsory payment, which, as you’ve learned, is a governmental prerogative. (Well, governments and extortionists.…)

Paul A. Samuelson, the first American winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics and sometimes called the Father of Modern Economics, encapsulated the argument in his classic text, Economics: An Introductory Analysis, first published in 1948 and re-issued in any number of editions. The pertinent quotes are:

Here is a later example of government service: lighthouses. These save lives and cargoes; but lighthouse keepers cannot reach out to collect fees from skippers.

And:

[G]overnment provides certain indispensable public services without which community life would be unthinkable and which by their nature cannot be appropriately left to private enterprise…. Take our earlier case of a lighthouse to warn against rocks. Its beam helps everyone in sight. A businessman could not build it for profit, since he cannot claim a price from each user. This certainly is the kind of activity that governments would naturally undertake.5

You, the red team member, convinced that scholarly knowledge is in no way analogous to lighthouses (being both rivalrous and excludable)—thus exempt from governmental appropriation—are happy with this reasoning: As sound and immutable as the fundamental constants of the universe—Like the speed of light! you blurt.

You, the blue team member, not so much, as you have “higher” ideals. Constants are made to be broken, you retort, followed by Information wants to be free!

To which the red team salvos: You have a problem with the speed of light?!

Sigh. But in the blue team’s favor, theoretical constants are made to be broken. Turns out … it’s complicated.

Enter a contrarian

Ronald Coase was a British-born American economist. Educated at the University of London External Programme, a distance-learning extension of the University of London—which Dickens called the “Peoples’ University,” as it offered higher education to the working classes—and then at the London School of Economics, Coase was a practical sort of man, more interested in what actually happens than theoretical constructions.

When he came to America in the 1930s on a scholarship, he researched the methods of business firms by actually traveling the country, meeting with business people, and asking them why they did what they did. Coase ultimately ended up at the University of Chicago Law School (not the Department of Economics), and won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1991.

Coase took up the issue of lighthouses in the 70s, and published his seminal article, “The Lighthouse in Economics,” in 1974.6 In it, he tested the economic dogma that only governments could overcome the free-rider problem presented by lighthouses. He did this by taking an historical approach: How had the building and maintenance of lighthouses actually been accomplished in England in the 17th through the early 19th centuries?

What he found was that stakeholders—non-governmental stakeholders—had in fact come together to provide the public good of lighthouses. Government’s role was limited to establishing and enforcing property rights in the lighthouses, just as it did for all other private property.

How did they manage it, you may ask? The historical case, as described by Coase, was as follows.

At an annual Lighthouse Conference, stakeholders met to determine the costs of providing adequate lights for the coming year. The stakeholders comprised two distinct groups: a Lights Advisory Committee; and three non-governmental bodies (NGOs, in today’s parlance) in England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland with authority over lighthouses, as conferred by the crown.

| Lights Advisory Committee | NGO authorities |

|---|---|

| Ship owners | Trinity House (England and Wales) |

| Underwriters | Commissioners of Northern Lighthouses (Scotland) |

| Shipping companies | Commissioners of Irish Lighthouses |

With a budget agreed, levies, known as light dues, were then assessed on ships calling at British ports to fund the construction and maintenance of lighthouses. The light dues were equitably distributed (based on ship tonnage7) and capped (dues were levied only on a specified number of voyages).

No attempt was made to assess dues on ships not calling at British ports but still benefiting from the coastal or hazard information provided by the lighthouses. Free riders.

So, if by some miracle you remember the list of mechanisms for overcoming free-ridership reviewed in Part 2…. No, of course you don’t. Here’s a review:

Mechanisms for overcoming free-ridership

- Selective incentives (or, exclusive benefits)

- Compulsory payments (taxation)

- Assurance contracts (subscriptions)

To which Coase added a fourth. Known as the Coasian solution, Coase claimed to have identified a mechanism whereby potential beneficiaries of a public good might collaborate to pool resources in the provision of that good without government intervention, provided the transaction costs were sufficiently low.

MENTAL HEALTH BREAK

Time for a quick mental health break.

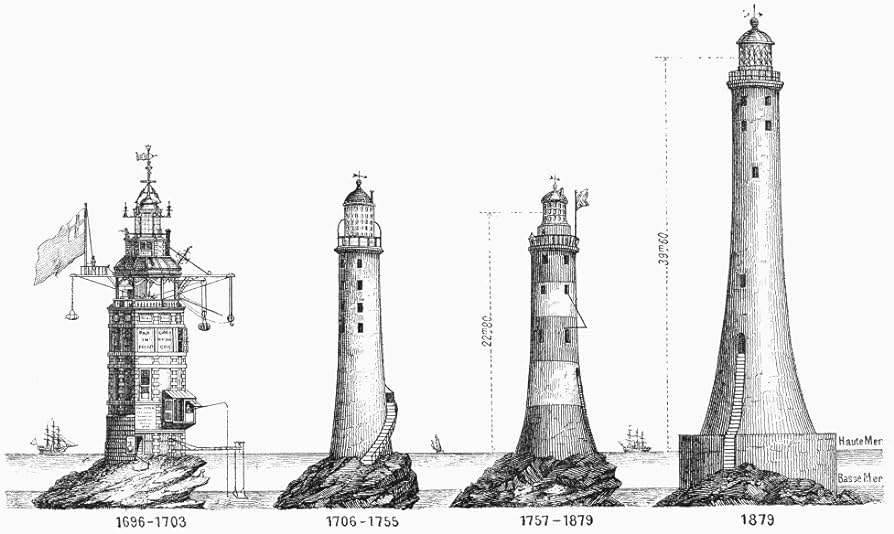

One of the lighthouses Coase offered as an example of private provision of a public good is the Eddystone, located on a reef 14 miles off of Plymouth. A dangerous reef, a woe to many ships. The image to the left above is a rendering of the first attempt to build a light tower on the reef by Henry Winstanley. Work began in 1696, and the lighthouse was dubbed “Winstanley’s Tower.” It was destroyed in a storm in November 1703.

A total of four Eddystone lighthouses were built over the centuries. After Winstanley’s Tower, which had a very short useful life (1698–1703) came Rudyerd’s Tower (1706–1755). Like Winstanley’s, Rudyard’s tower was built of wood. It stood for 47 years until the lantern caught fire, probably from a spark from one of the (… wait for it …) candles.

Next up was Smeaton’s Tower (1757–1879), built not of wood but of stone. Local granite was used for the foundation and facing, and Smeaton invented a quick-drying cement to seal the stones together. Smeaton’s tower stood for 120 years, ultimately being dismantled and re-erected on Plymouth Hoe, where it stands to this day.

The last Eddystone lighthouse is known as Douglass’s Tower, finished in 1882, also of stone but with larger blocks. It dwarfed its predecessors, rising to a height of 161 feet. In 1982 it was automated, a process that included adding a helipad above the lantern. It stands to this day beaming its warning to passing ships, under the control of Trinity House.

In 1697, when the English and the French were in one of their interminable wars, a French privateer abducted Winstanley, who was busily building his tower, and sailed to France with his captive in tow.

When Louis XIV heard of the incident, however, he ordered that Winstanley be immediately released, saying, “France is at war with England not with humanity.”

Of eggs and pudding

Samuelson was neither convinced nor amused. He claimed that Coase did not overcome the free-rider problem. Coase shot back as follows:

Samuelson says I was wrong and he was right, and he froths at the mouth when people talk about the lighthouse example. He says Coase is wrong; he doesn’t overcome the free rider problem. Who are the free riders? The foreign ships going past the British coast which do not call at a British port. Using Samuelson’s approach, what do you do? Do you ask the foreign governments to give you a subsidy? Do you tax people in Britain because the foreign ships are getting help without paying for it? What do you do? My approach is to compare the alternatives. People like Samuelson like to set up a perfect world and say that the market does not bring us to this point and imply that the government should do something. They stop their analysis at that point.8

Froths at the mouth… Nice one, Ron. Very collegial of you.

Coase’s point (however expressed) was that the Lights Advisory Committee did not eliminate free-ridership, but that, in at least one historical instance, the problem was overcome through the collective action of private stakeholders. That is, as transaction costs were low enough, they were able to ignore the problem.

In the years since publication of “The Lighthouse in Economics,” debating Coase’s model has become something of a cottage industry—which is an indication of his importance to the field. No one’s debating that post you made to The Scholarly Kitchen four years ago….

One of the most significant criticisms leveled at Coase is that he had a fairly … elastic … definition of “private enterprise.” Coase asserted:

The role of the government was limited to the establishment and enforcement of property rights in the lighthouse. The charges were collected at the ports by agents for the lighthouses. The problem of enforcement was no different for them than for other suppliers of goods and services to the shipowner. The property rights were unusual only in that they stipulated the price that could be charged.9

In fact, the government played a somewhat larger role than Coase suggested. It granted the lighthouse owner a monopoly, it set the schedule of dues and helped in their collection10—including by threatening fines or imprisonment on recalcitrant shippers. Additionally, “the lighthouse ‘owner’ did not have the right to enforce the payment of dues without the Crown’s authorization.”11

At best, lighthouse services surveyed by Coase constituted something more of a public-private partnership, and an inefficient one at that. In 1834, the House of Commons Select Committee on Lighthouses issued a damning report.

Your Committee have learned with some surprise that the Lighthouse Establishments have been conducted in the several parts of the United Kingdom under entirely different systems; different as regards the constitution of the Boards of Manage, different as regards the Rates or Amount of the Light Dues, and different in the principle on which they are levied. They have found that these Establishments, of such importance to the extensive Naval and Commercial Interests of this Kingdom, instead of being conducted under the immediate superintendence of the Government, upon one uniform system, and under responsible Public Servants, with proper foresight to provide for the safety of Shipping in the most efficient manner, and on the most economical plans, have been left to spring up, as it were, by slow degrees, as the local wants required, often after disastrous losses at sea; and it may, perhaps, be considered as a matter of reproach to this great country, that for ages past, as well as at the present time, a considerable portion of the establishments of Lighthouses have been made the means of heavily taxing the Trade of the country, for the benefit of a few private individuals, who have been favoured with that advantage by the Ministers and the Sovereign of the day.12

The historical example that Coase held up as a shining example of the private provision of a pure public good was neither private nor particularly good. It was, in fact, an “expensive and defective service.”13 In 1836, Trinity House was compelled by Parliament to buy out all remaining private lighthouses,14 effectively imposing governmental control. Trinity House itself remains a charity, but it is funded through Light Dues levied on commercial vessels calling at ports in the British Isles, based on the net registered tonnage of the vessel. The rate is set by the Department of Transport.

Coase over egged the pudding.

Marginalia

Just a couple of points to jot in the margin, to tidy things up…

…but wait. If you think about it, aren’t most artifacts of scholarly knowledge—books, textbooks, journal articles, data—simply jots in the margins of the accumulated book of human knowledge? How important is any single jot, and to whom?

You in your blue jersey smirk and agree. Yep. And why should we pay for that? And who would spend their lives publishing jots?

To which the red team retorts, If you think they’re so useless, why do you want everyone to have them? Followed by a muttered, (Those jots make your insufferable phone work….)

Sigh. You’re both about to be put in the naughty corner. Both of you. Together. Forever. Like Sartre’s hell.

The first point to tidy up is to note that there’s no tidiness to be had. Coase’s jot on lighthouses—taking direct aim at a Nobelist (Samuelson) before he himself was a Nobelist15—lit up a vigorous discussion on public goods. It was Samuelson, after all, who coined the term and established the modern economic theory. The debate swirls on and on (with the red team producing ever more related artifacts and the blue team begrudgingly paying for them).

One notable contribution was made by Tyler Cowan while a mere Ph.D. candidate at Harvard, in 1985. Cowan challenged Samuelson’s very definition (non-rivalrous and non-excludable), arguing that publicness and privateness are not inherent (“per se“) characteristics of economic goods, but are dependent on their institutional context and conditions of production. In short, any economic good could be classed as either “public” or “private”.

Insofar as the concept of a public good does survive, it should be remembered that publicness is an attribute of institutions, not of abstract economic goods. Every good can be made more or less public by examining it in different institutional contexts.16

So maybe this entire series is even more of a waste of your precious time than you had already likely concluded.

A second point in the interest of an unachievable tidiness has to do with marginal cost. An additional attribute of pure public goods sometimes included with the previously discussed two is that they have zero marginal cost in their provision, due to their non-rivalrous quality. To Samuelson, again:

Take our earlier case of a lighthouse to warn against rocks. Its beam helps everyone in sight… Because it costs society zero extra cost to let one extra ship use the service, hence any ships discouraged from those waters by the requirement to pay a positive price will represent a social economic loss – even if the price charged is no more than enough to pay the long-run expenses of the lighthouse.17

That Samuelson was describing a system of open-access provision of the good lighthouses provide—not unlike the scholarly jots you (plural) so vigorously debate—has been noted by at least one economist:

In modern terminology, it could be stated that Samuelson … described a system of ‘open access’, wherein tolls would be set to $0 (£0), to lighthouse services.

And:

The term ‘open access’ is used here in a manner similar to its use in terms of access to online (internet) versions of scholarly output (for instance, published journal articles).18

Which makes sense: in a digital environment, once the system is set up, the marginal cost of allowing one additional person access to a scholarly artifact is zero. Except, maybe not.

Marginal costs, even for lighthouses, may be non-zero:

The MC of the lighthouse is unlikely to be zero if: (a) the lighthouse does not simply mark the seaway, but also provides signalling services (for instance, fog signalling), rescue and ship registering services; and/or (b) light dues collection requires manpower. Marking the seaway is not costless, as fuel, transport, and administration are required. The variable cost of signalling includes, at a minimum, positive labour costs and equipment running costs, which could be avoided if the lighthouse was unmanned or not communicating with ships.19

Even you, in your sweaty blue jersey, must acknowledge that those in foul red jerseys provide more services than simply pushing out jots. And there are positive costs in running their platforms. You may have even learned this the hard way when you made the poor (and costly, and inefficient) choice to set up your ridiculous institutional repository.

Perhaps best to leave that marginalium unresolved, lest an endless number of posts appear on The Scholarly Kitchen made by yous who wouldn’t know a marginal cost if it bit them in the….

Jefferson’s taper redux

Recall, if you’re able, that the purpose of this series was to come to common agreement on terms. If fight you must, might be a good idea to know what you’re fighting about.

Has that been accomplished? (Give it some thought, because it’s complicated—or better still, enroll in a community college trade program and learn to do something useful, or take up golf….)

Maybe not, as even those who actually know what they’re talking about rarely agree (see the foregoing—all of the foregoing).

On the other hand, perhaps (adopting a dangerously optimistic posture) enough fog has cleared at least to see potential reefs in order to steer clear (is), even if the course forward is not entirely manifest. Potentially identifying options—feasible options—to pay for Jefferson’s taper?

And in so doing, making some progress in your common goal (you agreed in Part 1, as people of good will) of including scholarly jots in the ideal that knowledge ought be a common good, and societies should strive to make it so?

At which point, no doubt, general comity will break out, lions and lambs will lie down together (without one being in the other’s stomach), and you (both of you) could find something better to do than endlessly gnaw this tiresome bone.

- The Latinists among you may object from construing suum cuique tribuere to construe fairness. Which would only show what a pedestrian Latinist you are. ↩︎

- Interestingly, Smith was not only Scottish (a hotbed of Calvinism) but a devout Christian and a member of the Church of Scotland. He signed the Calvinist Westminster Confession of Faith before taking up his Chair at the University of Glasgow. Might that have influenced his theorizing? ↩︎

- As might be expected, unanimous agreement does not exist. “[W]hen economic theory comes to define economic history, as it has with respect to the lighthouse, important historical facts become overlooked by virtue of the fact that theory has defined their possibility out of existence. This has been the case with the lighthouse which was never non-rivalrous or non-excludable.” Rosolio Candela and Vincent Geloso, “Why consider the lighthouse a public good?”, International Review of Law and Economics 60 (2019), 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2019.105852. ↩︎

- John Stuart Mill, The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume III – The Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy (Books III-V and Appendices), ed. John M. Robson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press,1965), 376. ↩︎

- Paul Samuelson, Economics: An Introductory Analysis (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 45 and 159, respectively. ↩︎

- R.H. Coase, “The Lighthouse in Economics,” The Journal of Law and Economics 17 (October 1974), 357-76. https://doi.org/10.1086/466796. ↩︎

- Tonnage is a ship’s capacity, not the actual cargo it might be carrying on any voyage. So a ship of a certain tonnage might be carrying a full load of soybeans, a full load of gold, or nothing at all. The dues charged would be the same.

↩︎ - Thomas Hazlett, “Looking for Results: An Interview with Ronald Coase,” Reason Foundation, January 1997, https://reason.com/1997/01/01/looking-for-results/. ↩︎

- Coase, op. cit., 375. ↩︎

- David Van Zandt, “The Lessons of the Lighthouse: “Government” or “Private” Provision of Goods,” The Journal of Legal Studies 22 (1993), 56. https://doi.org/10.1086/468157. ↩︎

- Elodie Bertrand, “The Coasean Analysis of Lighthouse Financing: Myths and Realities,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 20 (2006), 9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bei068. ↩︎

- “Report from the Select Committee on Lighthouses; with The Minutes of Evidence,” Parliamentary Papers, Session 1834, Vol. XII, iii-iv. ↩︎

- Bertrand, op. cit., 10. ↩︎

- The process was not completed until 1842. ↩︎

- Samuelson was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1970. Coase was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1991). ↩︎

- Tyler Cowen, “Public Goods Definitions and their Institutional Context: a Critique of Public Goods Theory,” Review of Social Economy, 43:1 (1985), 62. 10.1080/00346768500000020. ↩︎

- Samuelson, op. cit., 159. ↩︎

- F. G. Mixon, Jr, and R. S. Bridges, R. S. III. “The lighthouse in economics: colonial America’s experience,” Journal of Public Finance and Public Choice, 33 no.1 (April 2018), 83 and n. 5, respectively. https://doi.org/10.1332/251569118X15214757915591. ↩︎

- Lawrence W. C. Lai et al., “The Political Economy of Coase’s Lighthouse in History (Part II): Lighthouse Development along the Coast of China.” Town Planning Review 79 (2008) 415. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.79.5.6.

↩︎