Image credit: Ἡγεμὼν εἰς τὰς γλῶσσας; id est, Ductor in linguas, The Guide into Tongues, 2 parts in 1 vol., (Printed by William Stansby and Eliot’s Court Press) John Browne, 1617

PART 2 of a series

The Goat called loudly after him and reminded him of his promise to help him out: but the Fox merely turned and said, “If you had as much sense in your head as you have hair in your beard you wouldn’t have got into the well without making certain that you could get out again.”

– Aesop, The Fox and the Goat

You’re all likely wearing your silly jerseys, chanting your teams’ chants. But maybe you’re beginning to wonder why. Maybe, you might be thinking, it’s more complicated than I thought.

That would be the hope.

Rational actors

A perennial problem in providing access to public goods and common pool resources is that of free ridership. It’s a type of market failure—an inefficient distribution of goods or services—that occurs when a shared resource is overused by people who aren’t paying their fair share or aren’t paying anything for the resource at all.

Simply put, individuals acting in their own self interest have no incentive for voluntarily contributing to the provision of a common resource if that resource can be consumed at no cost. The problem is exacerbated in times of economic stress. Derogatory as the term sounds, free riders are not necessarily selfish louts (though they may be); they are rational actors. Some of them might be poor—and ye have the poor with you always.

Economists and political scientists have identified a number of mechanisms that can overcome the free-rider problem under certain circumstances. One is by offering selective incentives—or more clearly put, exclusive benefits.

In the world of scholarly information, one could imagine setting up a system in which the content is free, but value-added services—maybe enhanced search functionality, consulting services, API service level agreements—are offered to supporting members, whose dues fund the cost of the good (open-access content). The Principles of Open Scholarly Infrastructure (POSI) attempt to codify just such a practice by asserting that revenue should be based on services, not data.

Interestingly, selective incentives can also be negative. For example, a publisher of scholarly information might choose to offer its content on an open-access basis, appeal to institutions worldwide to support the costs at specified amounts based on some metric (cost per use?—no, the blue team hates that),1 and flash nuisance notices to users at institutions failing to provide support. In a word, shaming, which can be an effective selective incentive in small, homogeneous groups.2 But the ocean you swim in is neither small nor homogenous.

Another mechanism is by compelling payment—a right commonly known as taxation and typically reserved to governments. Roads and national defense are obvious examples of public goods funded by compulsory payment. Extortion is another means of compelling payment….

A third is the use of assurance contracts. This is an interesting mechanism and worth exploring a bit. They work like this:

- Members of a group pledge to contribute to a collective good if a total contribution level is reached.

- If the threshold is met, action is taken.

- If the threshold is not met, no action is taken and any monetary contributions refunded.

Kickstarter, with which you may be familiar, works in just this way. Closer to the topic at hand, Subscribe to Open,3 a practical and refreshingly unideological approach to converting subscription journals to open access, is nothing more or less than an assurance contract.

Despite the rise of open-access in journal publishing (in all its various colors and forms), the subscription model remains the dominant method for funding the publication and dissemination of scholarly knowledge.4 Whatever your attitude toward subscriptions may be (the teams sharply differ), the model is so familiar that you likely think of it as a part of nature, like minerals or polar bears. But of course it is not. It is a human invention, a business model with a history—its origins in 17th century England.

Historically, books were very expensive luxury goods, and their production was typically underwritten by wealthy patrons. As were the libraries that housed them; think of the Library of Celsus in Ephesus, or the Library of Alexandria under the patronage of the Ptolemies.

But in 17th century England, the patronage system was slipping a bit; authors and publishers without independent means needed a way to assure their costs would be covered before incurring them. This was particularly true for expensive publications, such as atlases, geographies, histories and illustrated books. The solution that was hit upon was to solicit advance payment or guarantee of payment from “subscribers.” If enough subscriptions were purchased, the book would be produced, and if not, not. Sounds perilously close to an assurance contract, doesn’t it?

The first known book published by subscription was John Minsheu’s Ἡγεμὼν εἰς τὰς γλῶσσας, id est, Ductor in linguas, The Guide into Tongues,” an eleven-language dictionary published in 1617. Minsheu managed to secure nearly 400 subscribers, some from among the usual patron class, but others of lower rank, including one “citizen and grocer,” and Minsheu published their names in The Guide. This became common practice for subscribed books. (The title page and list of subscribers is pictured at the top of this post.)

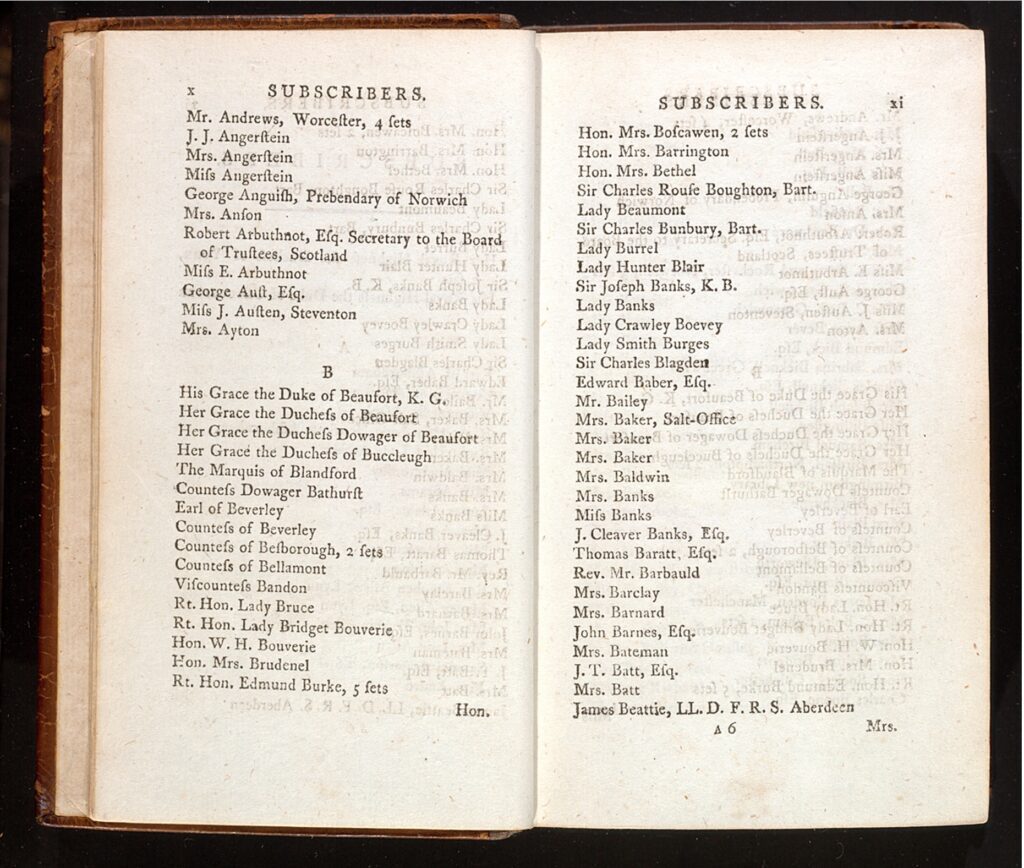

The image above is part of the subscriber list from Fanny Burney’s Camilla, published in 1796; the total list runs to 38 pages. Looks perilously close to a selective incentive, doesn’t it? And in fact it was. People looking to move up the social ladder and with sufficient resources willingly subscribed to a publication just to see their name in proximity with royalty and other illustrious persons. Selective incentives can be economic or, as in this case, social.

So the subscription publishing model developed in the 17th century employed two mechanisms now identified by economists as means to overcome the free-rider problem in the provision of public goods: assurance contracts and selective incentives.

But what kind of good was being provided?

Books, or at least the information and ideas contained in them, are non-rivalrous goods: one person’s knowledge of the plot of Camilla does not diminish another’s. But they are excludable: only subscribers got a copy of the book (and a shout-out on the subscriber list).

The requisite attributions of public goods reviewed in Part 1 of this series (non-rivalrous and non-excludable) are actually attributes of pure public goods, as distinct from purely private goods—the two extremes on the spectrum of goods. As you might expect, reality is somewhat more complex than these polar opposites suggest: there is a spectrum of ownership-consumption possibilities between the two, much as there are clines in population genetics.

Goods that are excludable but non-rivalrous are referred to by economists as club goods. And exactly what is a club good, you ask?

In economics, club goods—also sometimes referred to as scarce or artificially scarce goods—are a subset of public goods that possess one of the two key factors that public goods carry—namely, being non-rivalrous.5

Curious as you are, you further ask, And who or what provides club goods?

Clubs (of course). Like tennis clubs (but, confusingly, unlike golf clubs…). An unfortunate choice of terms, you think. It sounds frivolous. Fair enough, but the economic theory of clubs has wide reach.6

The definition of club, from the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, is:

[A]n organization that provides a shared collective good exclusively to its members, with the cost of the good being defrayed from member payments, typically in the form of dues.7

And as it turns out, clever John Minsheu and the subscription publishers that followed him did not manage to provide a pure public good, but a club good. Still, it is an admirable accomplishment; many great scholarly and literary works were produced by means of that business model—a risk-mitigation and cost-recovery model—that would likely never have been produced otherwise.

The subscription model was adopted for scholarly journals in the 17th century as well—that is, from the beginning—precisely to mitigate financial risk and assure the widest possible dissemination of research results. Journal subscriptions were originally assurance contacts in fact and continue to function as such, effectively providing a significant good. You might say a world-changing good.

If you take a moment to think a bit more, universities can be thought of as clubs as well, at least those that limit admissions (on whatever criteria) and charge tuition and other fees. They exercise excludability, and the services they provide—lectures, access to libraries and other resources—are generally non-rivalrous. In modern times, universities have become the engines of the greatest growth of knowledge in human history. Not so frivolous.

Club goods are not part of nature8—they did not grow on trees; they were developed by humans as innovations meant to overcome practical problems. Any number of different solutions might have been implemented. But what is done is done.

Now you, a member of the red team, may be satisfied with this arrangement, as it has produced a successful, scalable—and, in many cases, lucrative—model. Smugly satisfied, in fact.

You, a member of the blue team, are likely more than dissatisfied with the arrangement. At least insofar as subscriptions go (not so much tuition). Furious, in fact, as subscription costs are breaking your budget.

Which is precisely the problem: two opposing teams stuck in their ideological trenches.

Knowledge in the dock redux

To return to where this all began and in an attempt to share a common set of facts (exhausting all this, but it’s your frigging debate, not the rest of humanity’s, who have more pressing concerns, like golf, or figuring out how to pay for their kid’s tuition at your frigging institution, which includes access to your frigging publications)…. How is knowledge in general (and scholarly knowledge as a subset) to be scored in the economic matrix of goods?

| Type | Rivalrous | Excludable | Knowledge in general | Scholarly knowledge |

| Public good | ✗ | ✗ | – NO – | – NO – |

| Common good | ✔ | ✗ | – NO – | – NO – |

| Club good | ✗ | ✔ | – YES – | – YES – |

| Private good | ✔ | ✔ | – YES – | – NO – |

The matrix clearly excludes both knowledge in general and the subset you (both) care so deeply about from being understood as public or common goods. Impossible, due to the attributes of those goods that knowledge (both sorts) lack. That leaves the two options.

You learned in Part 1 of this series (if you have enough neurons rubbing together to be capable of learning) that the challenge Henry Oldenburg struggled to overcome was the inherent rivalrousness of knowledge, scientific knowledge in particular. And he was successful in that effort—so successful that, in these times, scholars are heavily incentivized to disseminate their research.9 So despite the fact knowledge in general can be both rivalrous and excluded—thus a private good (recall Jefferson: “…which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself”),10 in the context of scholarly knowledge, the problem of rivalry has been largely solved.

Which whittles options down to one: scholarly information remains inherently a club good, due to its attributes.

Measure twice, cut once

Even admitting that conclusion, perhaps grudgingly, mutual animosity persists between the camps.

And for good reason, as you’re both utterly ridiculous.

You in your silly blue jersey continue to fire off such utterances as “Information wants to be free!” or proudly wear buttons reading “I support tax payer [sic] access to publicly funded research.” Do you support tax-payer access to publicly funded tax-free institutions, like your university—the one that pays your salary?

And you in your hilarious red jersey continue to yawn on about the costs of publication and the value your activity adds, ignoring the extortionate rates some of your ilk have been charging on your monopoly products11—and the fact that you typically don’t pay your reviewers? Oh, and you might remember that you once sold books to libraries to be housed on the library’s shelves; now you sell libraries both the content and the shelves, and charge them every year.

Caught in the middle of all this ridiculousness is the vast majority of scholars (and their societies—the vast majority of which are tiny and struggling to keep their shirts on, financially). They plod on, advancing knowledge (in fits and starts, as that’s how it goes), mentoring students, working endless hours for little money. While you’re busy being … you, with all your passions. Good job.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be this way. Leaving oughts aside, you (plural) could declare an armistice, crawl out of your trenches and imagine a different is, one that widens access ever more, perhaps even universally, if feasible.

Aiding in that effort might be the observation (which should be obvious) that public goods don’t grow on trees any more than club goods. They are declarative goods, in the sense that societies collectively define what is to be included in that list. Which is just what Jefferson suggested:

[I]nventions then cannot in nature be a subject of property. society may give an exclusive right to the profits arising from them as an encouragement to men to pursue ideas which may produce utility. but this may, or may not be done, according to the will and convenience of the society, without claim or complaint from any body.12

So it’s a social decision to be made. Or it could be, swatting aside Smith’s invisible hand. If and as you consider alternatives, pause to recognize that the club-good model has proven to be remarkably sustainable and scalable for over four centuries, only experiencing significant dysfunction (you might say, market failure) in recent decades. That could be corrected without crashing the plane.

Aiming before shooting is always to be preferred.

Oldenburg did his bit. What remains to be solved, hopefully by mutual effort and to your mutual satisfaction, is how to pay for Jefferson’s taper, ever mindful “of ye Observance of ye Ole Law, of Suum cuique tribuere [to render everyone their due; fairness].”13

- E.g., Curtis Kendrick, “Guest post: Cost per Use Overvalues Journal Subscriptions,” The Scholarly Kitchen, 2019, https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2019/09/05/guest-post-cost-per-use-overvalues-journal-subscriptions/. ↩︎

- “In general, social pressure and social incentives operate only in groups of smaller size, in groups so small that the members can have face-to-face contact with one another.” Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collection Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), 62. ↩︎

- Developed by Raym Crow of SPARC. ↩︎

- Estimates of the percentage of open-access articles vary between 28 and 54%, depending on data source used. See Isabel Basson et al., “The effect of data sources on the measurement of open access: A comparison of Dimensions and the Web of Science,” PLOS One (March 31, 2022).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265545. See in addition “Trends for open access to publications,” European Commission, accessed January 2024, https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-2020-2024/our-digital-future/open-science/open-science-monitor/trends-open-access-publications_en.

↩︎ - “Club Goods,” Corporate Finance Institute, accessed January 2024, https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/club-goods/.

↩︎ - The theory was first developed in a seminal paper by James Buchanan: “An Economic Theory of Clubs,” Economica New Series 32 (February 1965) https://doi.org/10.2307/2552442. ↩︎

- M.C. McGuire, M.C., “Clubs,” in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (London: Palgrave Macmillan 1987) https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_660-1.

↩︎ - Of course, everything is a part of nature, but you get it. ↩︎

- They typically care more about disseminating it to colleagues, not the great unwashed, but that’s another story. ↩︎

- “Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson, 13 August 1813,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0322. ↩︎

- Well, not technically monopoly products. But practically so, as journal articles and the data underlying them are complements of one another, not substitutes. Any major university failing to subscribe to E–’s or W–’s resources would risk a faculty stampede. ↩︎

- Jefferson, op. cit. ↩︎

- The Correspondence of Henry Oldenburg: Vol.II 1663-1665 (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1966) 329. ↩︎