Image credit: Pilfered, source unknown

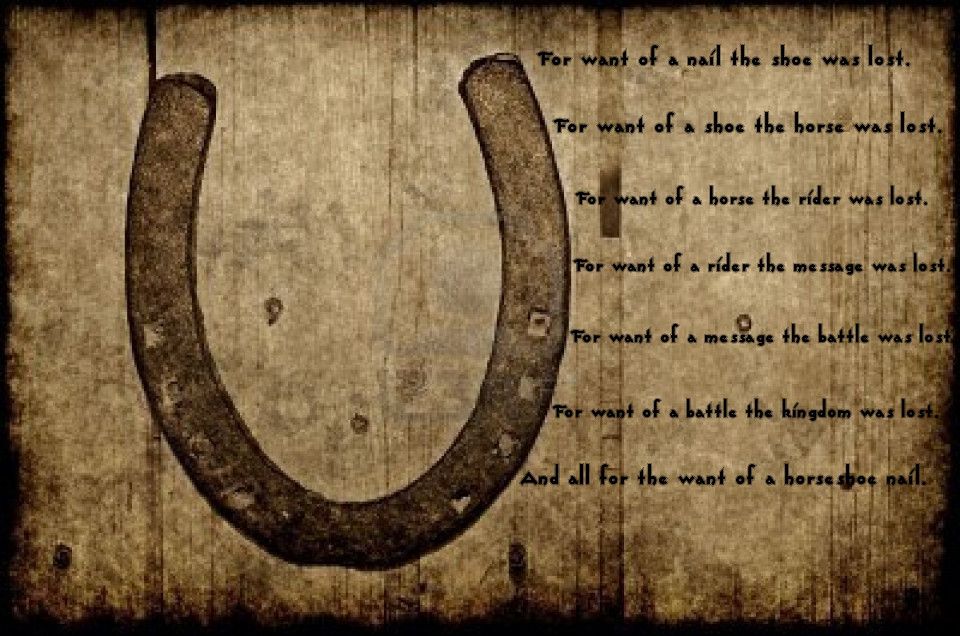

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

– Nursery rhyme and proverb, dating to the 14th century

Have you ever noticed how active the lips of educated speakers of the King’s English are? All those rounded vowels! God, their faces must be exhausted by the end of the day. No wonder they take baths at night.

If you’re American, you’re spared of all that effort (and can take showers in the morning). And if you’re from the Midwest, you’re spared further still. Because most vowels1—certainly a, e, and i—are sounded as schwas, which is a flat, neutral vowel sound represented by the phonetic symbol /ə/ and having the approximate sound value of eh. It is a marvel of efficiency.

Generally speaking, only diphthongs are reliably afforded the dignity of distinct sound values by Midwesteners. But not always. The second person pronoun (which for reasons beyond understanding is the same for both singular and plural, leading to all manner of inelegant2 workarounds such as, “y’all” or, worse, “all y’all”, or worse still “youz”) is often pronounced yeh. As in, Yeh thehnk?

A sure test in identifying a Midwestener is to attend to how they pronounce the definite article. It will invariably be sounded theh, unless they’re attempting to learn guitar by playing James Taylor songs (struggling with his strange tunings). Which requires cognitive coal to be burned to sound thee. Taylor always says thee—a certain indication that he is not a Midwesterner. Quod est demonstratum.

So, a tony Briton might say:

Wail, yew mawst be pleesd with yorself.

Whereas you would likely say:

Wehl, yeh mehst be pleezd with yehrsehf.

Of course you’re pleased with yourself, whatever your nationality. That’s what yous do!

The Midwestern solution to vowels is a marvel of efficiency, except when it comes to spelling. For example, is it independent or independant? No difference in pronunciation (efficiency) but critical difference in spelling (requiring mental effort, more coal shoveled into the cerebral cortex: memorization). But what’s the worst that can happen? Independant is just a misspelling. You’ll look like a dope. Anything new there?

More troubling are confusions such as eminent and imminent, as, though identical in pronunciation (for Midwesterners), they have utterly distinct meanings. Imagine what might happen if you, a Midwestener, were (Heaven forfend) a field agent who had received intelligence on a missile launch, the nature of which must be communicated by secure, written comms to the Pentagon….

Or, if Hamlet had a similar confusion in his pilfered and redacted missive to King Claudius, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern….3

As it turns out, it’s not just words that matter, but the spelling of words.

H.W. Fowler had much to say about English usage. His signal Fowler’s Modern English Usage is worth consulting here:

em- and im-, en- and in-. The words in which hesitation between e- and i- is possible are given in the form recommended.

Embed, empanel, encage, encase, enclose etc., encrust (but incrustation), endorse, endorsement (but indorsation), endue, enfold, engraft, engrain (but ingrained), ensure (in general senses), entrench, entrust, entwine, entwist, enwrap; insure (in financial sense), insurance, inure (but enure for the legal word), inweave. See also IM-.

Tenacious clinging to the right private judgment is an English trait that a mere grammarian may not presume to deprecate,4 and such statements as the OED’s The half-latinized enquire still subsists beside inquire will no doubt long remain true. See INQUIRE. Spelling, however, is not one of the domains in which private judgment shows to most advantage, and the general acceptance of the above forms on the authority of the OED, undisturbed by the COD, would be a sensible and democratic concession to uniformity.5

(And you thought you had a respectable vocabulary. When was the last time you used entwist?)

On Fowler’s considerable authority, then, conformity is preferred. Democratic, even. That, no doubt, is why God created spelling correctors.6

Truth be told, English is a mess of a language, King’s version or otherwise. Especially when it comes to vowels (consonants are mostly safe). No one was more aware of the mess than John Chadwick, University Assistant Lecturer at Cambridge University. Chadwick was a philologist (the modern term is linguist) and classicist.

Americans in general—and Midwesterners in particular—typically assume that that sort of person must be somewhat (or a lot) effete. Pale, limp-wristed, myopic. But in point of fact, Chadwick, while enrolled at Cambridge in his first year (1940) studying Classics, left to volunteer for the Royal Navy. He served in the Mediterranean as an ordinary seaman aboard the HMS Coventry. His ship was torpedoed by an Italian submarine; it was dive-bombed. At some point, one of his superiors must have noticed his intelligence, as he was summoned for an interview by the Chief of Naval Intelligence, whereupon he was promoted to Temporary Sub Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve and tasked with cracking Italian codes. If that weren’t enough, he was then sent to Bletchley Park (the English manor house that had become a hive of Allied code-breakers), managed to learn Japanese and cracked Japanese encoded messages.

And you have done what? So much for Americans and their priors.

One of Chadwick’s enduring scholarly interests was the Bronze Age Aegean script Linear B. No one had cracked that. In fact, no one had cracked any of the Bronze Age scripts—because they made no sense for Mycenaean Greek, the earliest known form of the Greek language.7 Chadwick and some colleagues attempted to apply their cryptographic dark arts to Linear B’s decipherment but ultimately gave up and moved on to other pressing concerns. Like publishing an edition of The Medical Works of Hippocrates.

Chadwick was aware, however, of the work of a rank amateur, Michael Ventris, who was also working to decipher Linear B. Ventris was an architect and a self-taught philologist. He was convinced that Linear B was a Greek script (not some other Mediterranean language)—a distinctly minority view. Chadwick, intrigued by Ventris’s discussion of Linear B on a BBC Radio broadcast, contacted Ventris and offered his help as a “mere philologist.”

This led to a collaboration over the next four years and the publication of a foundational journal article on Linear B8 and then a book, Documents in Mycenaean Greek.9 Ventris had indeed cracked the code and was awarded the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for his efforts.10

The collaboration ended abruptly in 1956, when Ventris managed, one late night, to smash his car into a parked truck. He was 34. The coroner’s verdict was accidental death….11

Why was Ventris’s achievement so lauded? And why did it take an amateur, rather than a specialist, to crack the code? Because Linear B is a syllabary, not an alphabet. And Greek cannot be easily expressed in a syllabary. It leads to all sorts of ridiculous configurations, like pa-te for patēr (πατήρ, father) a-to-ro-po for anthrōpos (ἄνθρωπος, human being, person).

Though eventually convinced, nearly all scholars were initially skeptical of Ventris’s conclusion (that Linear B was in fact a Greek script). And fair enough, ridiculous as its use for Greek was. Chadwick was less put off, noting that Linear B functioned as a mnemonic device, much like English, with the latter’s though, through, thought nonsense. And:

Pudding, puddle, putting. Putting? Yes: at golf it rhymes with shutting.12

English, like Linear B, is such a mess that it might be called chaos. Which indeed it has.

Why? The reason is that English was in the midst of a vowel shift when Gutenberg created his horrible machine. The Great Vowel Shift it’s called, so momentous as to be designated by a proper noun phrase. Even the best English users were hopelessly confused. Shakespeare is the spelling we know as authoritative for The Bard, but he himself seemed unsure of how to spell his name. In his signatures it appears, variously: Shaksper, Shakspeare, Shakspere.13 If Johannes could have exercised just a bit of patience, things may have sorted themselves out.14

Vowels were flying all over the place. The long vowel in the Middle English word sheep, for instance, had the sound value of shape. But with the vowel shift, it took on the value of beet, thus sheep. ās became ays (as in name), īs became ais (as in time), ō became a diphthong pronounced ow (as in house) and so on. It was chaos. The Chos, in fact. And thanks to a certain German goldsmith, it remains a mess.

The Shift lasted for what felt like forever, from 1400 to 1700. Two things are strange about The Great Vowel Shift: First, no one knows what prompted it in the first place, or what kept it going for such a long time. Second, the English managed to push it along without tipping into a civil war. Which itself is strange because, first, the English have a history of being prone to civil wars (usually about religion, but still); and second, because humans fight wars over language routinely.15

You would think that, dragging that mess along with them, Brits would have remained confined to their Emerald Isle, unable to communicate effectively with themselves, much less the rest of the inhabited planet (…for want of a vowel the empire was lost…). And you would be very much wrong. At its height, the British Empire occupied 24% of Earth’s land area. It was the largest empire in history. And even today, nearly 20% of humans speak English as a first or second language. How do they manage it? How do you manage it? Needs must?

For all that you have the Brits to thank. That and Calvinism.

- Setting aside y, which in English is a mess of an identity crisis. ↩︎

- Or is it inelegent? ↩︎

- Uh, over egging the pudding here? You know: Tom Stoppard, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, play, 1966? Your 9th grade teacher may have made you read it? Never mind. Oh, and if you think any of the foregoing bears any particular resemblance to reality, seek professional help. Immediately, if not sooner. Except the James Taylor bit; that might be about right. ↩︎

- Or is it depricate? ↩︎

- H.W. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, 2nd ed. (New York and Oxford, 1965), 154-55. ↩︎

- Like many of the deity’s creations, spelling correctors are both a gift and a curse. A gift as they obviate the need for memorization; a curse as they befuddle learning and personal improvement. They can also make fairly embarrassing corrections. ↩︎

- There are four such scripts. Along with Linear B are Linear A, Cypro-Minoan, and Cretan hieroglyphic, the latter three remaining uncracked to this very day. ↩︎

- Ventris, Michael, and John Chadwick. “Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Mycenaean Archives.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 73 (1953): 84-103. doi:10.2307/628239.

↩︎ - Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953). ↩︎

- As the award has it, “services to Mycenaean paleography.” Ventris was also awarded the title of honorary research associate at University College, London, and an honorary doctorate of philosophy from the University of Uppsala. ↩︎

- If you’re a cynical sort, you might wonder whether you-altering chemicals were involved. ↩︎

- Gerard Nolst Trenité, Drop Your Foreign Accent: Engelsche Uitspraakoefeningen (Tjeenk Willink, 1929). ↩︎

- Typing of these examples demonstrates just how much of curse spelling correctors can be. ↩︎

- To be fair, it would have taken quite a lot of patience. More, in fact, than his mortal coil had to offer. ↩︎

- See Sam Quillen “War of the Words: How Language Has Sparked Almost Every European War Since 1870.” Medium. April 15, 2022. https://sjquillen.medium.com/war-of-the-words-how-language-has-sparked-almost-every-european-war-since-1870-effc7f5269ac.

↩︎