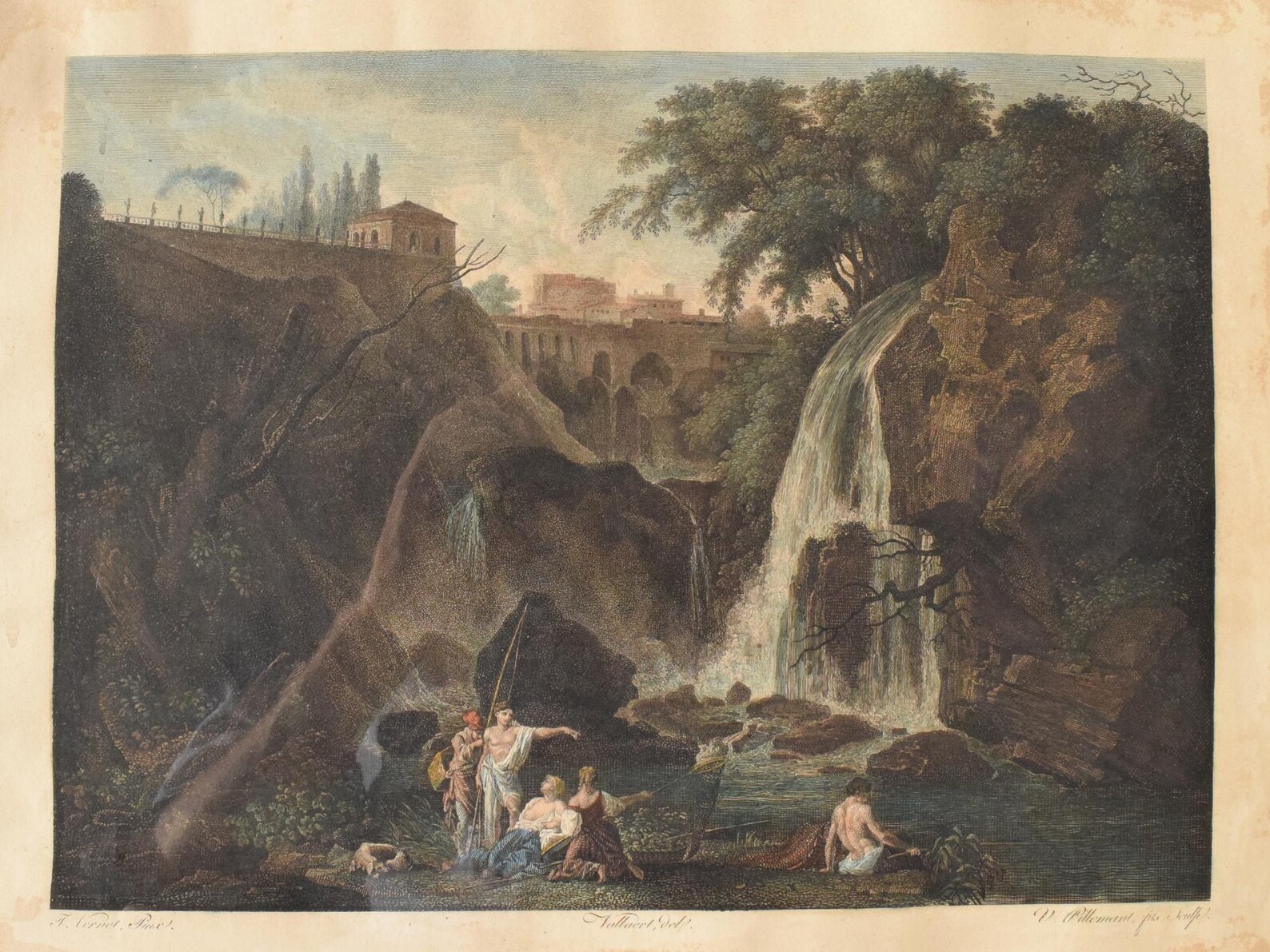

Image credit: The Waterfalls at Tivoli Drawing (1714–1789) – Claude-Joseph Vernet

part 4 of a series

Men with chests

“Then I am a religious man, Pendrick, as every sane man must be. It may be, I fancy, that I have seen more of the ways of this world’s Maker than you,—for I have sought his laws, in my way, all my life, while you, I understand, have been collecting butterflies.”

–H. G. Wells, The Island of Doctor Moreau

You have to acknowledge that you have some affection for C.S. Lewis. You have fond memories of reading the Chronicles of Narnia as a child. You had a boxed set. And, for an Apologist, he was in certain ways less strident than some of his co-Apologists; he seemed to have a more generous understanding of the efficacy of his evangel’s blood. Hell was only the worst of you winning the moment, always a reversible condition. Even some worshippers of Tash were welcomed into Aslan’s heaven—appalling to evangelicals, nearly as heretical as Rob Bell’s Love Wins.

Orthodox Christians know perfectly well that love does not win. The angels did not proclaim, on the event of the evangel’s birth, “Peace on Earth, good will to men”; it was “Peace on Earth to men to those on whom his favor rests”1—a nontrivial difference. The great white throne of judgement remains grimly in place.

However much “nicer” Christians, the “Jesus followers” (Christians without chests, the Orthodox might say), downplay that little troubling hole below the waterline on their enchanted ship. That … and hell, slavery, genocide, rape…. The woes that inevitably accompany the blessings.

Nietzsche and Lewis’s intellectual trajectories could be characterized as “crossed foils.” Well, could have been, had they been contemporaries—or characters in a Shakespeare play. Neither of which they were. Where did you learn that concept? In middle school, of course. From Ms. Rab, who was famous for being a delight the first half of the year and something to the contrary the second, said fame having been realized in your experience.

And what utility did knowledge of that concept offer you, throughout your life? Yet another question that answers itself in the asking.

In brief, Nietzsche, whose plan had been to study theology, lost his god and the objective values that went along with him. The European morals of his day had been invented by resentful Christians, having inherited the odious Jewish tradition, to control their noble betters. Far from objective, values were contingent, the Judeo-Christian variety enervating to the health of the species—even poisoning the blood of the race.2

Lewis, an atheist, found his god and not only a belief in objective values, but a belief that objective values could be demonstrated. To be fair to Lewis, the Natural Law he discovered was not initially restricted to the Christianity he affirmed; they were universal, transcending cultures and present in the great literatures of all traditions. In his lecture series given at Durham University, he termed the Natural Law the Tao. He gave three lectures, the last titled, “The Abolition of Man,” which gave the published compilation its title.

See? Crossed foils. Ms. Rab would give you a gold star (if it were first semester…).

(It should be noted that nine years later Lewis pressed the “Law of Nature,” no longer the Tao, into service in his apology for “mere” Christianity. So.)

What moved Lewis to give his lectures, compile them into a book(let), publish them, and consider the publication “almost my favourite among my books”?3 What lit him up? you wonder.

The first thing that might be said is that Lewis was ever ready for ignition. When an atheist, he was a particularly foul-mouthed one. As an Irishman, it took him years to accommodate himself to the “demonic” English accent and the Sceptered Isle’s hideous landscape. Maybe because his father was a cold fish, maybe because of his experience of trench warfare in WWI, maybe because of his 1943 perspective—with Hitler and Stalin rising—he was or became a petrol-soaked pile of kindling, eager to toss the match used to light his pipe on his pile of grievances, real or perceived. In short, he was a chesty sort.

In this particular case, it was a book on elementary education that came into his hands and thence to his shelf (details as to just how are unclear), specifically its second chapter, where he quotes the offending authors, to whom he has graciously given pseudonyms:

In their second chapter Gaius and Titius quote the well-known story of Coleridge at the waterfall. You remember that there were two tourists present: that one called it ‘sublime’ and the other ‘pretty’; and that Coleridge mentally endorsed the first judgement and rejected the second with disgust. Gaius and Titius comment as follows: ‘When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall . . . Actually . . . he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word “Sublime”, or shortly, I have sublime feelings. … This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.’4

Upon reading that, you think, But of course … how could it be otherwise? A waterfall is nothing more than a physical phenomenon. Anything beyond that is what a sentient creature might bring to it. Would a waterfall on a lifeless planet have any inherent sublimity?

Whereupon you’re tempted to think you’ve read far enough. And not all temptations are unto evil. But, you have some capacity for curiosity (which you often find irritating)—and people you actually know and respect (or, at least, like) think Lewis is all that. So you soldier on, and soon find the nub of Lewis’ objection:

The reason why Coleridge agreed with the tourist who called the cataract sublime and disagreed with the one who called it pretty was of course that he believed inanimate nature to be such that certain responses could be more ‘just’ or ‘ordinate’ or ‘appropriate’ to it than others. And he believed (correctly) that the tourists thought the same.5

So, a waterfall on a lifeless planet … Is that his argument? Indeed so:

The man who called the cataract sublime was not intending simply to describe his own emotions about it: he was also claiming that the object was one which merited those emotions.6

But … what a ludicrous argument to make! At which point you find yourself muttering expletives.

What Lewis found, with Coleridge, so disgusting about Gius and Titus’ teachings is a philosophical theory popular in the early 20th century called “emotivism”. Moral statements reflect nothing more than one’s emotional reactions. To find something good is nothing more than to say “Hooray”; to find something bad is nothing more than to say “Boo”. Emotivism has a long pedigree in philosophical thought; it can be found as early as the 18th century in the writings of George Berkeley and David Hume. To the latter, “Morals and criticism are not so properly objects of the understanding as of taste and sentiment.”7

Though currently out of fashion, accusations of a dishonest adherence to emotivism continue to be made: “…to a large degree people now think, talk and act as if emotivism were true, no matter what their avowed theoretical standpoint may be.”8

So, you think, mentally sighing in fatigue of Christian accusers, now I’m an emotivist, whether I admit it or not….

Which, of course, you’re not. You don’t have to be an emotivist to think that an unobserved storm on Mars has any quality that merits …anything. It just is.

Humans assign values to their physical environments as they do to entities in their markets. And the values they bring might differ depending on temperament or predicament; the eye of the beholder. To take the waterfall example, one might find it sublime in Edmund Burke’s sense, “the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling,”9 or one might find it pretty (say, if its mists produce rainbows). If one found oneself in a rudderless boat on a river rushing toward the cataract, one might find it terrifying.10 The waterfall in and of itself is none of those things.

What got Lewis’ Irish up was his concern for the education—or miseducation—of schoolboys. To be taught that their value judgments were nothing more than subjective expressions of their emotional states was not only demonstrably wrong but ruinous to society. Just how ruinous he elaborates in the third and final lecture: a cadre of social engineers or “Conditioners”, freed from all traditional morals, will inevitably emerge and use malign scientific tools (eugenics, psychological conditioning, etc.) to produce a docile race, easily manipulated in pursuit of the Conditioners’ goal of domination.

Not unlike what Nietzsche imagined Christianity had done to create the weak herd, creating an opportunity for the noble Übermenchen, you note, pleased with yourself for connecting those dots.

Like thinkers before him concerned with the proper education of boys, Lewis needed a good metaphor to press his point. Knowing his Plato, he had one at hand. In the Phaedrus, Plato imagines the human soul as follows:

We will liken the soul to the composite nature of a pair of winged horses and a charioteer. Now the horses and charioteers of the gods are all good and of good descent, but those of other races are mixed; and first the charioteer of the human soul drives a pair, and secondly one of the horses is noble and of noble breed, but the other quite the opposite in breed and character. Therefore in our case the driving is necessarily difficult and troublesome.11

One horse represents noble impulses and passions, the other the opposite. The charioteer represents the intellect, which must wrangle the horsey impulses pulling in different directions on a journey of enlightenment.

But Lewis was no fan of enlightenment, or at least the Enlightenment. He thought (wrongly) that the scientific revolution spawned by that cultural disaster was the fraternal twin of magic, driven by a common impulse to control nature and arising at the same time in history. And whereas magic had failed, science achieved a lamentable success:

Now I take it that when we understand a thing analytically and then dominate and use it for our own convenience, we reduce it to the level of ‘Nature’ in the sense that we suspend our judgements of value about it, ignore its final cause (if any), and treat it in terms of quantity. … We do not look at trees either as Dryads or as beautiful objects while we cut them into beams: the first man who did so may have felt the price keenly, and the bleeding trees in Virgil and Spenser may be far-off echoes of that primeval sense of impiety. The stars lost their divinity as astronomy developed, and the Dying God has no place in chemical agriculture. To many, no doubt, this process is simply the gradual discovery that the real world is different from what we expected, and the old opposition to Galileo or to ‘body-snatchers’ is simply obscurantism.12

No more Dryads? No divine stars? Enchantment “Hooray”, Science “Boo”? Indeed so:

It might be going too far to say that the modern scientific movement was tainted from its birth: but I think it would be true to say that it was born in an unhealthy neighbourhood and at an inauspicious hour. Its triumphs may have been too rapid and purchased at too high a price: reconsideration, and something like repentance, may be required.13

So Lewis needed a different metaphor to describe the human condition, one not ruled by intellect, which denatures the natural world with its jaundiced gaze; Plato’s rational charioteer would not do. Men (it’s always men with Lewis) need chests to mediate between their heads, the locus of intellect, and their bellies, the locus of appetites. (Bellies and parts further south, you think, somewhat indelicately.)

The head rules the belly through the chest. … It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal.14

What the boys needed to make them chesty was to have proper, objective and universal virtues beaten into their pubescent heads. “The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust, and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likeable, disgusting and hateful.”15 You better not call that waterfall ‘pretty’…. Failing such a pædogogy, society, having sown the wind, will reap the whirlwind:

We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.16

In short, if emotivism was the disease, virtue ethics was Lewis’ cure.

The world has never lacked for men with chests, filled with whatever iteration of Dieu et mon droit they might lay claim to. The Roman kind, the Jewish kind, the Persian kind, the Chinese kind, the Aztec kind, the English kind…. The Jewish kind, the Christian kind, the Islamic kind…. Warlords, kings, emperors, priests, prophets, pastors. Whatever; same as it ever was.

The evangel himself (now the Pantocrator) was pretty chesty himself to whomever crossed his ideological line. Pharisees, Sadducees, scribes.

What would Lewis, you wonder, think of all the chesty Christians now in circulation? Charlie Kirk, J. D. Vance, Pete Hegseth, Ross Douthat, William Lane Craig… Of the many Christian churches and madrassas that were, are and ever have been male-ruled and chesty?

You shudder to think. (He might approve….)

That having been said (or exorcised), everyone is a hostage of their time, which might require you to adopt a more charitable view than is your wont, stormy-mooded as you typically are when in the company of Apologists. And, if you’re honest, in general.

Lewis gave his lectures in 1943, just after the Blitz, where the ghastly apex of Nietzsche’s philosophical project—on one not entirely unfair reading of it—ruled the skies. The war was far from won. Planes rained down bombs, both products of a science that might indeed require something like repentance. It’s easy, then, to imagine his horror at what the triumph of Nietzschean perspectivism had brought to pass. It must have seemed a genuine apocalypse.

And you have no problem with virtue ethics. Pubescent boys are pre-human maniacs, frontal cortices in lagging formation, in need of schooling (or jailing). All societies practice virtue ethics in their pædogogies of that feral pack, as well they should. What distinguishes Lewis is not his advocacy of virtue ethics; it is his assertion that there is a set of virtues that transcend time and space, that there is a unified notion of the behavioral good, that there is only one sort of chest that is properly to be built.

That would be a neat trick, you think. Whence cometh these virtues? But at the moment, other demands enjoin your time. There are drinks to be made, dinner to be had, a show to be watched. The fragile butterflies of a contingent life to be collected.

- Luke 2:14: δόξα ἐν ὑψίστοις θεῷ καὶ ἐπὶ γῆς εἰρήνη ἐν ἀνθρώποις εὐδοκίας. For an approachable discussion of the Greek, see Andreas Köstenberger, “Peace on Earth, Good Will Toward Men?”, Biblical Foundations, n.d., https://biblicalfoundations.org/peace-earth-good-will-toward-men/. ↩︎

- Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, trans Michael A. Scarpritti (Penguin, 2013), ‘Good and Evil’, ‘Good and Bad’ §9: “Let us submit to the facts; that the people have triumphed – or “the slaves”, or “the masses”, or “the herd”, or whatever name you care to give them – if this has happened because of the Jews, so be it! In that case no nation ever had a greater mission in the world’s history. The “masters” have been done away with, and with them their aristocratic morality has vanished; the morality of the low classes has triumphed. This triumph may also be called a blood-poisoning (it has blended the races) – I do not dispute it; but there is no doubt but that this intoxication has succeeded.” ↩︎

- C. S. Lewis to Mary Willis Shelburne, 20 February 1955 in, Lewis, Collected Letters, Vol. III (HarperCollins, 2007), 567. ↩︎

- C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (HarperCollins, 2009), 2–3. ↩︎

- Lewis, Abolition, 15. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- David Hume, An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, ed. Peter Millican (Oxford University Press, 2007), §12.33, p. 120 ↩︎

- Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 3rd ed. (University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 22. ↩︎

- Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, (Oxford University Press, 1990), §7, Of the Sublime. ↩︎

- Important to note that Burke identified terror as the source of the sublime: “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. I say the strongest emotion, because I am satisfied the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those which enter on the part of pleasure.” Idem. ↩︎

- Plato, Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9, trans. Harold N. Fowler (Harvard University Press, 1925), §§246a and 246b. ↩︎

- Lewis, Abolition, 69–70. But wait, you think, isn’t domination of nature what is god commanded? “And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth” (Gen 1:28). You shake your head. Side issue. Rabbit trial. Set it aside. ↩︎

- Lewis, Abolition, 78. ↩︎

- Lewis, Abolition, 25. ↩︎

- Lewis, Abolition, 16. ↩︎

- Lewis, Abolition, 26. ↩︎