Editors’ introduction:

After an unusually long interval between the fifth and sixth posts in this series, we queried the author as to when the final installment might be expected (having suffered through the first five in the series and eager to put the ordeal to rest). Receiving no reply, we undertook further inquiries–only to learn that the author had expired. He was, on the account given by his wife, found head down at his desk. An autopsy was ordered as the death seemed in need of explanation, no significant morbidities having been previously identified.

The results were … puzzling. No physical insult could be identified to explain the untimely passing: cardiac, pulmonary, vascular, gastrointestinal or cerebral. The ‘Immediate Cause’ on the death certificate was given as “Unspecified natural causes.” The sequential etiology leading to the immediate cause was given as “Likely despair or exasperation due to inordinate concentration on a tiresome matter.” (The author’s wife, interviewed by the authorities, had described the decedent’s literary efforts over the preceding months.)

After expressing our sincere condolences, we inquired of the widow whether the author might have left any notes pertaining to the sixth and final installment of the series. We were hopeful of an affirmative answer, as the author had previously informed us, in an excited manner, that he had solved the vexing problem of open access (but gave no details as to how this signal achievement might have been accomplished beyond the claim that his model had reached “Nash equilibrium”).

The widow–who, it must be said, seemed more than somewhat relieved that her long ordeal with the author had come to an end–indicated that indeed yes, all manner of scribblings, notes, drafts and “whatnot” had been found beneath the head laid upon the desk. We further asked if she would be so kind as to remit whatever materials pertinent to the sixth and final installment to our offices, so that we might consider salvaging them for publication. She indicated that she would be more than happy to be rid of them (and their memory).

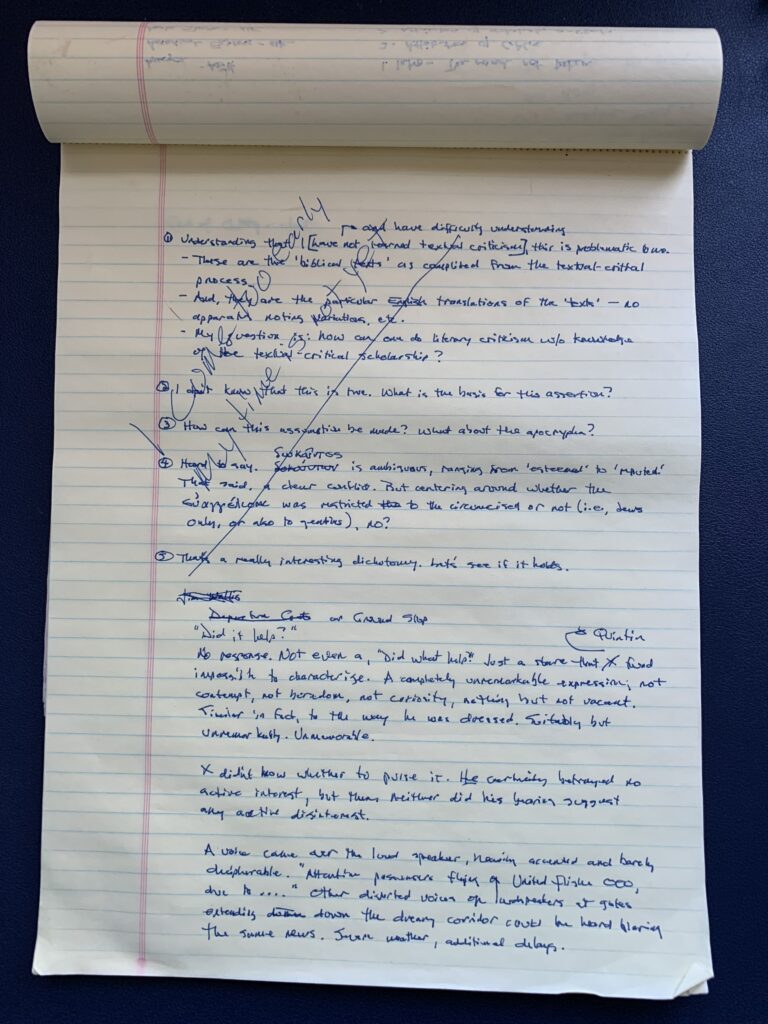

Some time later we received by post a large brown envelope containing a legal pad, a Moleskin notebook, and various single sheets of paper (some torn in half)–all filled with the author’s fine handwriting, some notes and drafts on the final installment, others on subjects seemingly unrelated. The last page of the legal pad had superimposed diagonally on various scribblings the words, “I come too early. My time is not yet”–an apparent reference to Nietzsche’s Parable of the Madman. (A photograph of the page is shown to the right.)

What follows is the author’s efforts on the sixth and final installment of the series, transcribed as faithfully as possible and edited for clarity. Bracketed headings indicate editorial attempts at organization. We leave it to the reader to judge the worth of the author’s effort in solving the intractable problem of open access.

[Apparent introductory quotation (undated)]

For the life of me I cannot remember

What made us think that we were wise and

We’d never compromise

– The Verve Pipe, The Freshman

[Overarching thoughts (dated February 2024)]

The open access movement as it has developed over the past two decades has largely failed to distinguish knowledge from knowledge artifacts, thereby subverting its own declared goals to provide a global public good. The peer-reviewed, published journal article, produced by the services academic publishers provide, remains the essential artifact upon which the good rests.

Fundamental distinctions (Datarob for the first three):

- Data: Data are plain facts, observations, statistics, characters, symbols, images, numbers, and more that are collected and can be used for analysis.

- Information: Information is the set of data that has been processed, analyzed, and structured in a meaningful way to become useful.

- Knowledge: Knowledge connotes the confident theoretical or practical understanding of an entity as well as the capability of using it for a specific purpose. Combination of information, experience and intuition leads to knowledge, which creates the potential to draw inferences and develop insights, based on experience, and thus it can assist in decision making and taking actions.

- Knowledge artifact: Knowledge artifacts are physical or digital manifestations of knowledge, recorded and managed as tangible recordings of knowledge to facilitate transmission to others.

No mechanism for distributing private knowledge publicly can do so without employing a knowledge artifact. This model identifies the artifact whose value represents the minimal tangible expression of the aggregate knowledge of authors and reviewers: the final accepted manuscript. This leaves room for third parties to add value, producing more refined knowledge artifacts (e.g., the published article, presented in polished ways, interlinked with other artifacts presented in related groups [journal], linked to related articles, etc.). The more refined artifacts and associated services may then be offered for sale in a market.

The model attempts to provide a club good (in hopes of ultimately providing a pure GPG) not based on an ideological commitment (“knowledge should be a public good”) but for entirely practical purposes (as expressed in the positive externalities enumerated by OECD). Following that, even countries which have shown no particular interest in open access as an ideological end may nevertheless be incentivized to join the model for reasons of national self interest.

[List of model attributes and outline (undated)]

Model attributes

- Recognizes the international nature of scholarship, thus the need for an international mechanism to extend access

- Recognizes the inherent characteristics of knowledge (rivalrous and excludable) and leverages them to produce a significant and expanding good

- Recognizes that gold OA (endorsed both by the UK and Plan S) does not solve for the monopoly problem inherent in scholarly knowledge, which leads to extraordinary rents charged by copyright holders

- Recognizes that green OA, as currently configured, does not provide a public good, as IRs are often not open to individuals not members of university clubs with access to gated IRs

- Recognizes that the wide dissemination of scholarly knowledge is an essential driver of collective economic growth (non zero sum)

- Establishes a club good (not a pure public good) representing, at the outset ~53%, of scholarly output (citable documents) globally

- Applies selective incentives to

- Block free riders

- Incentivize participation (thus extension of the club and the good it provides)

- Supports the work of academic societies and encourages decoupling from commercial interests

- Eliminates charges and other transaction costs to researchers

- Allows commercial interests to be pursued, but only based on the value they add via services

- Encourages commercial activity that extends beyond established artifacts of scholarly activities (e.g., KG/LLM models for various purposes built on the information contained in the corpus)

- Decouples knowledge from knowledge services

A modest proposal (the model)

- A modest proposal (the model)

- OECD member countries sign a binding legal instrument stipulating the following:

- The final accepted manuscript and descriptive metadata (including identification of the journal in which the manuscript is to be published) of all scholarly journal articles funded in whole or in part by governmental expenditure of signatories must be deposited in a central repository, established and maintained by OECD.

- Underlying data associated with the works must be deposited in an open data repository.

- The works to be maintained under a CC-BY license.

- Unique PIDs will be assigned to all manuscripts to allow citation.

- The works to be made freely available to citizens/legal residents of all countries signing and enforcing the instrument, irrespective of OECD membership.

- The works to be excluded from countries not signing or enforcing the instrument.

- Compliance to be strictly monitored and enforced by withholding future funding to non-complying researchers

- Selective incentives offered to commercial funders of research for entities operating in member countries:

- Due-free membership, subject to all requirements excepting annual dues

- Tax incentives for commercial R&D tied to compliance

- Academic societies [Optional, not critical]:

- Receive a small subsidy (Light Dues) on each citable work for which they have managed peer review.

- Progressive scale based on ‘tonnage’ (i.e., capacity), as represented by articles published in the PY; subsidies largest for smallest publishing capacity (to assist smaller societies).

- The subsidy would be funded by signatories to the formal instrument and any earnings on API SLAs.

- Subsidies not applicable to societies publishing with commercial entities.

- Academic publishers (irrespective of corporate structure):

- Free to sell subscriptions to entities in non-signatory countries

- Free to produce marketable products and services based on the value added to the government-funded research (e.g., workflow systems, copyediting, coding and typesetting, bibliometric services, etc.)

- Other entities would be eligible to build products based on the information contained in the repository (rate-limited API access free; increased limits via SLA agreements; derived data only)

Problems

- Incentivizing participation by commercial funders of research

- Compliance enforcement is applied at the level of the researcher, but efficient compliance requires publisher action (automated deposit of the final accepted manuscript and provision of a metadata file).

[Fragmentary draft (February 2024]

A road not taken

The open access movement as it has developed over the last two decades has moved from focusing on the costs associated with journal subscriptions (the “serials crisis”) to a call for scholarly knowledge to be declared a public good. What has been largely lacking in the open access discussion is a consideration of the economics of public good provision on a global scale. Such a consideration would need to take into account the inherent attributes of scholarly knowledge and the mechanisms available to provide a global public good (GPG). Ideological declarations (such as “Knowledge should be a public good”) are unfit for purpose.

The most important of the many formal open access statements that have been published are the Budapest Declaration, the Bethesda Statement and the Berlin Declaration. Each of these contain language that can be properly understood to declare scholarly knowledge, at a minimum in the form of journal articles,1 as GPGs (see Appendix A). None of these statements suggest how that goal might be accomplished beyond noting the possibility of global dissemination presented by the Internet, and recommending advocacy and encouragement for stakeholders to explore alternative routes to open access (e.g., self archiving, the establishment of new open access journals).

This proposal follows a divergent path. It represents an attempt to take the attributes of scholarly artifacts—the vehicles for dissemination of scholarly knowledge—seriously and explore practical mechanisms available to instantiate a new social norm, wherein scholarly knowledge becomes in fact a public good on a global scale. Thus, the approach is a pragmatic, rather than ideological, one.

The model proposes provision of a club good initially, whose members comprise nations which have recognized the practical benefits that open access to scholarly knowledge would confer, as expressed in the positive externalities enumerated by OECD (NOTE). Selective incentives encourage growth in club membership, to include countries which have shown no particular support for open access but join for reasons of national self interest.

The attributes of global public goods

The primary attributes of public goods were identified by Paul Samuelson seventy years ago (Samuelson 1954). Collective-consumption goods, in Samuelson’s formulation, are non-rival (one user’s consumption does not diminish another’s) and implicitly non-excludable (available to all, payers and non-payers alike). The archetypal example of a pure public good has long been the lighthouse. The coastal information its light provides is non-rival and, as a practical matter, tolls cannot be collected from passing ships benefiting from the lighthouse (thus, non-excludable), which proscribes private provision. In his classic Economics: An Introductory Analysis, Samuelson [1964, 159] employed the archetype:

But even if the [lighthouse] operator were able—say, by radar reconnaissance—to claim a toll from every nearby user, that fact would not necessarily make it socially optimal for this service to be provided. Why not? Because it costs society zero extra to let one extra ship use the service; hence any ships discouraged from those waters by the requirement to pay a positive price will represent a social economic loss—even if the price charged to all is no more than enough to pay the long-run expenses of the lighthouse. If the lighthouse is socially worth building and operating—and it need not be—a more advanced treatise can show how this social good is worth being made optimally available to all.

Not only did provision of pure public goods fall naturally to governments, Samuelson argued that it should be provided at a cost equal to the marginal consumer cost, which, in the case of the light from lighthouses, is zero. Samuelson was thus suggesting an open-access model for providing social goods [Mixon and Bridges, 2018], provided that a society found the benefits worth the costs.

GPGs share with public goods the attributes of non-rivalry and non-excludability but rarely in as extreme a manner as in Samuelson’s formulation of collective-consumption goods. That is, GPGs can exhibit some rivalry and excludability, making them impure GPGs [Buchholz and Sandler, 2021; see also Appendix B]. Unlike public goods, GPGs also possess the attribute of transnational spillover effects. This presents unique challenges in their mechanism of provision, or aggregation technology [Buchholz and Sandler, 2021].

For example, GPS systems provide benefits globally as aids to navigation, not unlike lighthouses. The U.S. Department of Defense built the first GPS system in the 1970s, which became fully operational in 1993. The aggregation technology employed was “best shot,” whereby the country providing the largest share of the good determines the aggregate level of provision—in this case, the U.S. government acting alone. The system included a feature which allowed the accuracy of its coordinates to to be degraded at any time, preventing enemies from using it for precise targeting. Called Selective Availability (SA) [Swider et al., 2000] , only authorized users (the Department of Defense, military allies and the like) with the appropriate key could correct the random errors introduced algorithmically by SA to correct coordinates. Thus, the U.S. system recognized the rivalry inherent in the global good it provided and introduced an exclusion mechanism. After SA’s employment against the Indian military in 1999, a number of entities, including China, Russia, Japan and the EU, built their own, independent GPS systems.

Transnational spillover effects also exacerbate the problem of free riding, whereby consuming nations can reap the benefits of the GPG while contributing nothing to its provision. With traditional public goods, free riding can be overcome by government provision via compulsory taxation. That is not an option for GPGs, as there exists no global governing body with taxing authority. Aggregation technologies, of which there are many, are simply strategies meant to overcome the unique challenges inherent in the provision of GPGs. Typically, these strategies require coordination among a number of countries to contribute to a GPG, which often involve novel institutional arrangements.

The attributes of scholarly artifacts

Ideas, in an abstract sense, may not be rivalrous. One person’s knowledge of a novel’s plot in no way diminishes another’s. This is often noted by open-access advocates in referencing Jefferson’s famous phrase, “he who lights his taper at mine in no way diminishes mine” [Jefferson 1813]. What is less often noted is that Jefferson was well aware that ideas could be reserved (thus excludable). His phrase only applied to knowledge divulged, and even in that case, he was sorely mistaken. Abstract ideas need a means of conveyance if they are to be of wider use; they need to be encoded for transmission—in books, articles, recordings, computer code and so on. Put differently, ideas need to become knowledge artifacts; else, they remain private knowledge.

- The Berlin Declaration is more comprehensive: “We define open access as a comprehensive source of human knowledge and cultural heritage that has been approved by the scientific community.” [Berlin Declaration 2003]. ↩︎