Image credit: Untitled, Nineta

PART 5 of a series

Now, comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short.

– George Orwell, Animal Farm

“Let’s face it…” must rank as one of the most arrogant (and ineffective) ways to engage in a discussion, as it implies that your interlocutor is not facing it. That being said, facts have a certain insistence, and arrogance in stating facts and insisting they be faced is sometimes in order. Like with flat Earthers.

As in this case, with you (both) wearing your ridiculous jerseys, shooting spitballs at each other, rather than working toward some sort of settlement. Like flat Earthers. Or ideological brats.

That a) having been said and b) needing to have been said, maybe you (both) could pull in your horns for a moment and have a look in the mirror? Think that’s possible? After all, you did agree in Part 1 that you, as people of good will, should strive to make scholarly knowledge as widely available as possible. A little honest self reflection may aid in that effort.

The mirror’s gaze: red team

If you’ve been paying any attention, red team, you’ve likely found some of the foregoing somewhat embarrassing. You certainly should have.

For instance, having learned that a certain Guardian journalist got a former CEO of MacMillian to out a former CEO of Elsevier by relating the latter’s saying the quiet part out loud: it’s all about adding the least value possible to garnish the greatest profit possible.

“And then we buy it and we stop doing all that stuff and then the cash just pours out and you wouldn’t believe how wonderful it is.”1 Remember? If not, review Part 4.

Prepare for further embarrassment.

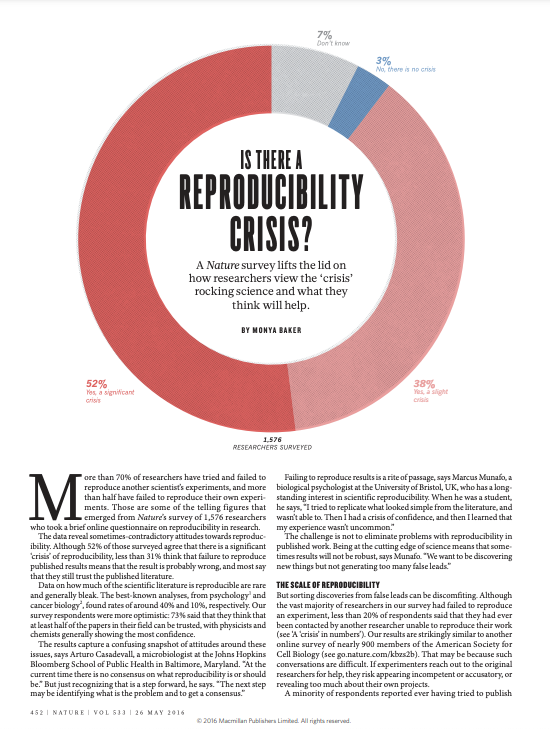

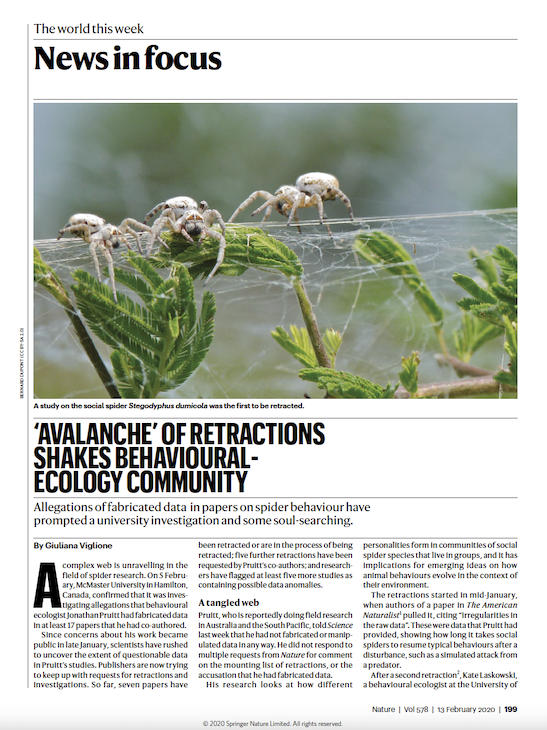

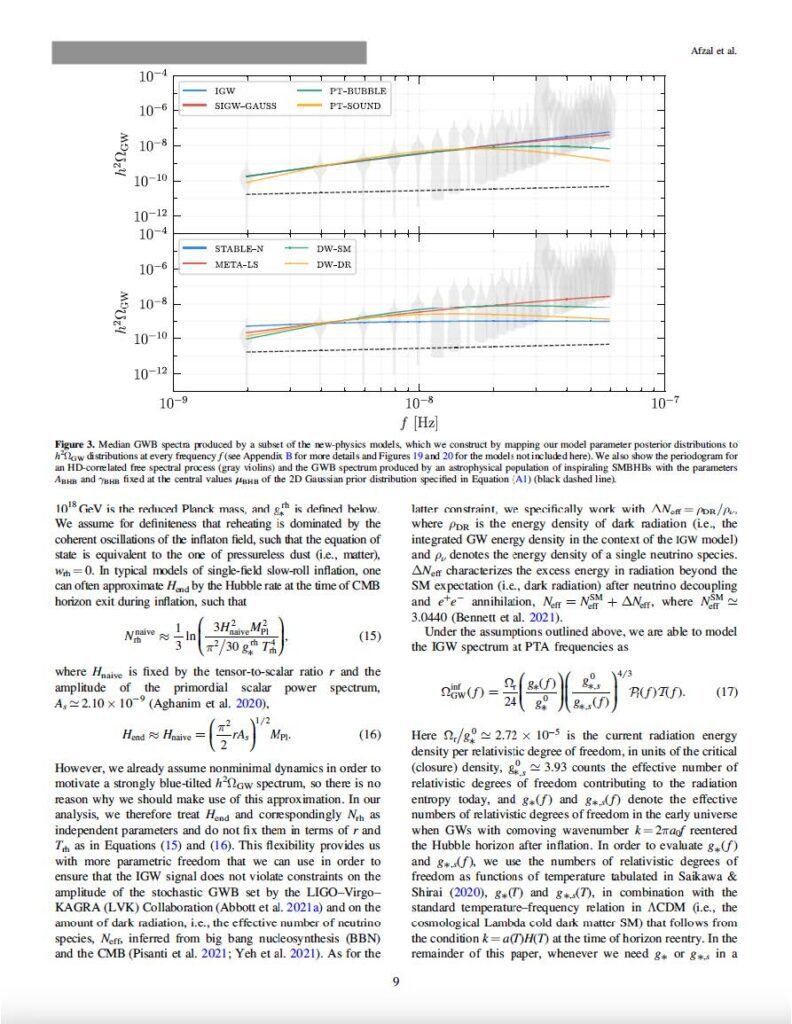

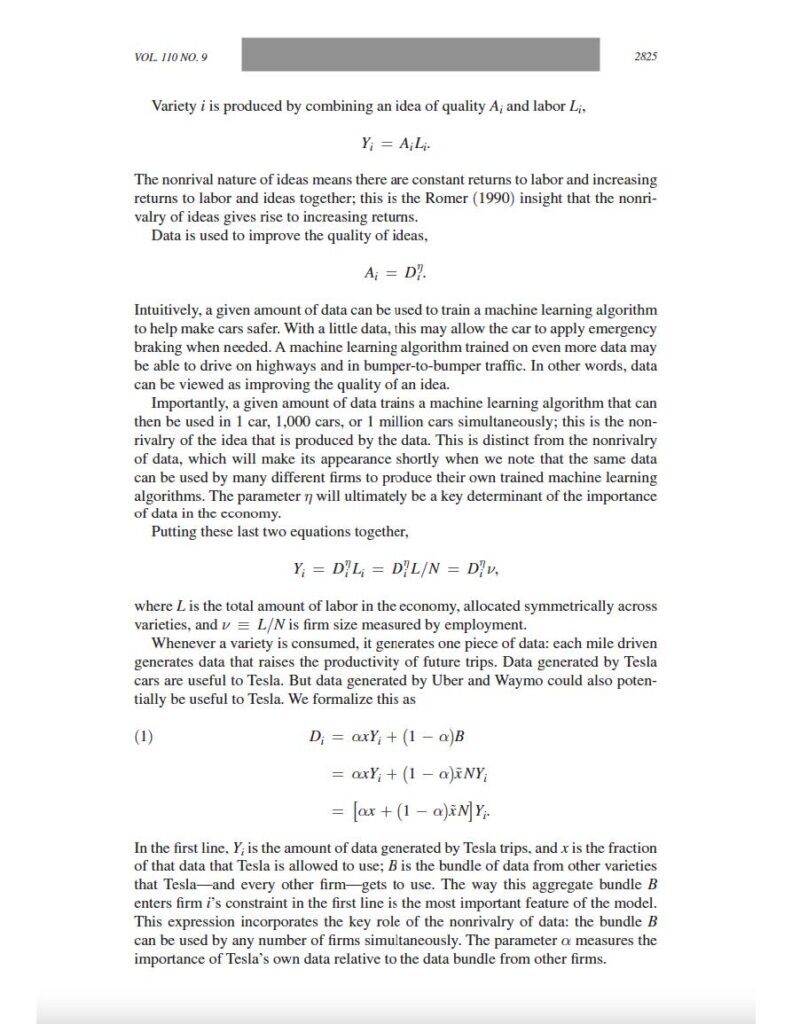

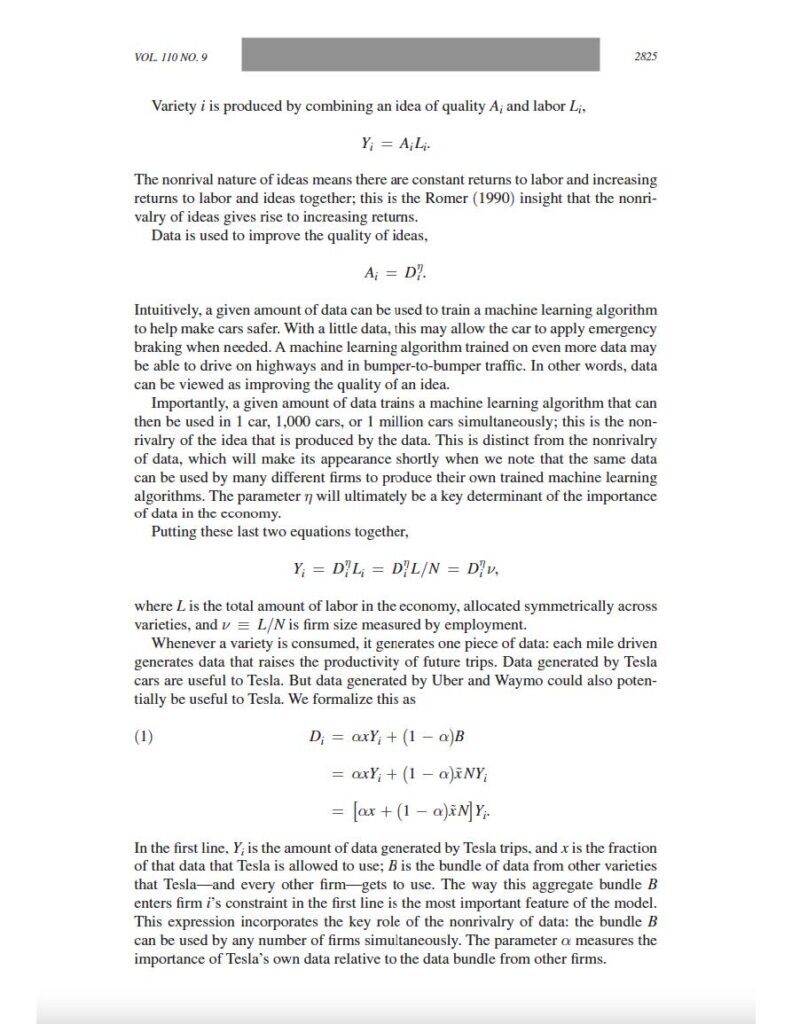

Have a look at the six images above. Five are pages from your own jots casting some considerable doubt on the value of your services—the provision of which leads to your extortionate profit margins. (The sixth, bottom left, is from Retraction Watch.)

While you are unquestionably better at publishing than philosophical scholars (congratulations for clearing such a low bar), you’re not nearly as good as you claim to be. A 2016 survey of 1,576 researchers found that more than 70% of researchers failed to replicate research results of other scientists.2 A number of fields are having acute replication crises, notably biomedical research and the social sciences. Not a positive trend, given that science’s claim to authority rests in no small part upon replicability, as Karl Popper observed long ago:

We say that a theory is falsified only if we have accepted basic statements which contradict it (cf. section 11, rule 2). This condition is necessary, but not sufficient; for we have seen that non-reproducible single occurrences are of no significance to science.3

You should find it cold comfort that 73% of scientists reported to be confident that at least half of the papers published in their fields could be trusted.4 You might want to read that again. Let it sink in.

Add to that a few more discomfiting developments: the hemorrhage of retractions of late; recent, high-profile cases of fraud and data manipulation;5 the growing “fake paper” phenomenon.6 And then this teeny weeny problem: your encouragement of the fine-slicing of scholarship, facilitating the publication (and sale) of ever more jots—most of marginal value or false7—is correlated with a decline in disruptive science:

In summary, we report a marked decline in disruptive science and technology over time…. We attribute this trend in part to scientists’ and inventors’ reliance on a narrower set of existing knowledge.… Relying on narrower slices of knowledge benefits individual careers, but not scientific progress more generally.8

Good job.

A last couple of pins to stick in the doll (charmingly fitted out in a red jersey):

- Your customers hate you (irritating as they may be); an outcome not typically desired by service providers.

- When your profit margins—largely taxpayer funded—head toward 40%, you’re just begging to be regulated.

The mirror’s gaze: blue team

And you, blue team, may also have found some grounds for embarrassment in the foregoing, assuming attention has been paid.

For instance, having been outed for endlessly quoting Jefferson’s remarks on his taper without bothering to read the entire letter to MacPherson, thereby misconstruing the quote entirely. Or having been exposed for paying precisely zero attention to the economics of what you’ve been so loudly advocating.

Prepare for further embarrassment.

Consider the four images above. They are pages from journal articles in four distinct disciplines. Are you able to meaningfully understand any of them? All of them? Can you even identify their fields of research?

Put differently, how important is it that you have access to these articles? Would reading them add to the sum total of your knowledge? Think of these pages as tapers. Would any of them actually light yours? Would all of them?

Put still differently, people have varying abilities to consume public goods due to factors like knowledge and skill. Technically known as variable consumption capacity, it doesn’t change the classification of the good as public (as it is not a formal characteristic of public goods), but it might give you pause as to the actual utility that your preferred solution would provide.

And then there are the negative externalities that your proposed solution, open access, has produced: predatory publishing, unequal utility due to variable consumption capacity (which can lead to misinterpretation and misinformation), additional transaction costs associated with moving from a reader-pays to an author-pays (or proxy-for-author pays) model, etc.

Not to mention the catastrophic financial consequences for academic societies publishing on a cost-recovery basis and not a profit-maximizing basis. To paraphrase a prominent consultant in the field, “Societies are being asked to jump out of the plane and build the parachute on the way down.”9

And speaking of finances, the tuition and fees charged by your academic clubs has grown at a CAGR of 6.06% from 1977 to 2023.10 That is nearly twice the inflation rate and well higher than the rate of growth in the number of journals catalyzed by HWSNBN and his ilk.11

Perhaps the most embarrassing point of all is the sheer hypocrisy of your position. If you were genuinely committed to Jefferson’s proposition, “…as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening mine”—that is, knowledge is a pure public good—you would transform your academic clubs into pure public goods, throw open your classrooms, labs, and libraries to all comers. Like Athena transformed the Erinyes into the Eumenides.12

You might then, rather than cherry-picking, fully embrace Jefferson’s vision:

[T]hat ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benvolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point; and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement, or exclusive appropriation.13

But it’s really not about an ideology of knowledge; it’s about money. Your broken budgets, the “serials crisis,” all that.

Swords into ploughshares

Well, that was unpleasant for you both. But transforming swords into ploughshares involves … beating. Apologies.

Perhaps, as you may have gained a bit more perspective than you had upon beginning this dreary journey, the time has come to work collaboratively toward an achievable compromise. That would be the hope.

Part 6 (the last in the series, you’ll be relieved to know) presents a proposal for open access that takes the inherent characteristics of scholarly knowledge seriously, separates knowledge in the form of ideas from knowledge artifacts, and strives to consider the interests of both teams. All in an attempt to work toward achieving Oldenberg’s vision:

…yt I thence persuade myselfe, yt all Ingenious men will be thereby incouraged to impart their knowledge and discoveryes, as farre as they may, not doubting of ye Observance of ye Ole Law, of Suum cuique tribuere [“allowing to each man his own, fairness”].14

- Stephen Buranyi, “Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science?” The Guardian, June 27, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science. ↩︎

- M. Baker, “1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility,” Nature 533, (2016): 452, https://doi.org/10.1038/533452a. ↩︎

- Karl Popper, Logik der Forschung (Vienna: Verlag von Julius Springer, 1935). Translated as The Logic of Scientific Discovery (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 66. ↩︎

- Baker, op. cit., 453. ↩︎

- E.g., Matt Egan, “Harvard cancer institute moves to retract six studies, correct 31 others amid data manipulation claims,” CNN, January 22, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/22/business/harvard-dana-farber-cancer-institute-data-manipulation-claims/index.html. ↩︎

- See e.g., Katharine Sanderson, “Science’s fake-paper problem: high-profile effort will tackle paper mills,” Nature Briefing, January 19, 2024, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00159-9 and Jeffrey Brainard, “Fake scientific papers are alarmingly common,” Science, May 9, 2023, https://www.science.org/content/article/fake-scientific-papers-are-alarmingly-common. ↩︎

- John P. A. Ioannidis, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” PLOS Medicine (August 2005), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. ↩︎

- Mark Park et al., “Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time,” Nature 613, 142–43 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05543-x. ↩︎

- No, this will not be attributed. ↩︎

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Measuring Price Change in the CPI: College tuition and fixed fees,” last modified February 9, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/college-tuition.htm. ↩︎

- See Part 4. CAGR in the number of journals between 1955 and 2020 was 3.6%. ↩︎

- You know, Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy? The transformation of the old blood-sucking Furies into the Gracious Ones, instituting a new and more just social order? ↩︎

- “Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson, 13 August 1813,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0322. ↩︎

- See Part 1. The Correspondence of Henry Oldenburg: Vol.II 1663-1665 (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1966) 327-9. ↩︎